DIVERSE AND ECLECTIC FUN FOR YOUR EARS - 60s to 90s rock, prog, psychedelia, folk music, folk rock, world music, experimental, doom metal, strange and creative music videos, deep cuts and more!

Saturday, August 3, 2024

The Shazam - Time 4 Pie

The Shazam are a criminally under-recognized power pop band hailing from the unlikely home of Nashville, Tennessee. They released four LPs between 1997 and 2009, as well as a few EPs and contributions to myriad tribute albums. Firmly on the ‘power’ side of the power pop genre, the Shazam’s sound is an amalgam of Cheap Trick, Material Issue, the heavier tracks on the first Big Star record, and the Who, infused by a healthy dose of ˈ70s glam from the T. Rex or Sweet playbook. At their best, the band and its frontman Hans Rotenberry manage a ridiculous number of earworm hooks, particularly on their essential second album.

The band’s self-titled 1997 debut is surprisingly self-assured, alternating between boisterous rockers that seem to make a bid for arena performances and more restrained, jangly, mid-tempo pop. Not everything hits, but the ratio of sing-along (or belt-along) choruses to less memorable tracks is pretty high for a power-pop long-player. Oh No in particular makes for a compelling band introduction, an energetic anthem that quickly establishes Rotenberry’s gift for radio-ready hooks, while showing off the joyously Keith-Moon-influenced drumming of Scott Ballew (who sadly passed away a few years back). Engine Red is more straightforward pop, a clever indictment of the party-crashing drunk that shows the band to be more lyrically amusing than most of their peers. Other winners like the gentler Megaphone, the anthemic Hooray For Me, and the glammed-up Florida, highlight the band’s stylistic range.

They took a huge leap forward on 1999’s Godspeed The Shazam, arguably one of the finest, most consistent power pop albums ever recorded, nearly every song offering at least one killer hook (if not more) that will be stuck in your head for days. It’s almost impossible to choose a few favorites for a Top 10, but the most obvious pick is Sunshine Tonight, a gleeful bit of Sweet-like high-energy bubblegum, easing from the slow burn of its verse to its chorus exhortation, “Everybody’s falling on their asses, come along ‘cuz it’s a gas gas gas!” Chipper Cherry Daylily offers a similar blast of light-hearted silliness tethered to giddy bubblegum, while the goofy City Smasher veers into a bass-driven faux metal groove with a sly insertion of a Surf City shout-out, over-the-top ridiculousness that demands wall-shaking volume. But the lighter, hook-crazy Calling Sydney and infectious lighter-hoisting power ballad The Stranded Stars, not to mention the whimsical post-election Super Tuesday – another spotlight for Rotenberry’s lyrical twists – are no less compelling.

The 2000 EP REV9 was a bit of a stop-gap pending their next album, a grab-bag of relative oddities. Lead-off track On The Airwaves is heavy-duty glam-pop that would have worked fine on Godspeed, with its blend of spooky theremin and a nicked Rush riff; and Month O’ Moons is cowbell-driven fun. But there are also some quiet ballads and stranger, more experimental tracks, most notably the studio goof Revolution 9, which updates the Beatles’ original with a rocking outro.

They returned in 2003 with Tomorrow The World, shaking off some of the daftness of the EP for a worthy (if less consistent) successor to Godspeed. Tomorrow’s peaks replicate the amped-up pop glory of its predecessor. Gettin’ Higher, like Sunshine Tonight before it, sounds like perfect fodder for Top 40 radio in an alternative universe where riveting guitar rock still has a place on the AM dial (plus, more cowbell!). We Think Yer Dead is rollicking fun, reprising the goofiness of City Smasher, while Nine Times stands firmly in comfortable power pop territory. Goodbye American Man (borrowing a riff from Big Star’s Don’t Lie To Me) and New Thing Baby sound like great lost 70s FM dial hits, all power chords and thunderous rhythm section.

The band took a few years off after that, returning in 2009 for the somewhat lackluster Meteor. Rotenberry comes up a bit short in the hooks department, resulting in a few tracks that feel more like underwhelming hard rock than the effervescent power pop of past work. Still, the album offers a few solid tracks. Hey Mom I Got The Bomb is silly fist-pumping fun, as is lead-off track So Awesome and NFU (as in, “not f*cked up enough”).

Sadly, Meteor was to wind up the band’s final proper album. However, it received a surprising coda with 2010’s Mountain Jack, which paired Rotenberry with the Shazam’s longtime producer Brad Jones (a power pop legend in his own right, with a lengthy resume as an artist and production whiz). It’s much more laid back than the heavy Meteor, peppered with acoustic guitars, and the hooks are more abundant. While the duo share vocal duties, it sounds like a stripped-down Shazam record, songs like Froggy Mountain Shakedown in particular worthy of inclusion in the Shazam discography.

Over the years, scattered among various tribute albums and online releases, the band also put together a nice assortment of covers worth tracking down, ranging from the Who’s I Can See For Miles to Shoes’ Hangin’ Around With You to Teenage Fanclub’s The Concept, all faithful to the originals with jolts of added energy. Word was that the band regrouped later in the decade for a new album, but Ballew’s passing in 2019 seems to have put the kibosh on further work, though one song from the sessions, the moody It’s Doomsday, Honey, streams on Spotify. From: https://www.toppermost.co.uk/the-shazam/

Niyaz - Minara

Singer Azam Ali was born in Iran, raised in India, and now lives with her Iranian husband, Loga Ramin Torkian, in Los Angeles. Their journey across oceans can be heard in their music. With producer Carmen Rizzo, they created a group called Niyaz, which means "yearning" in both Farsi, the language of Iran, and Urdu, the main language in Pakistan. Niyaz released it second album, "Nine Heavens," this year. It begins with a piece called "Beni Beni," which combines a mystical 18th-century Sufi poem with a traditional Turkish folk song and electronic music.

LIANE HANSEN: Azam and Loga are in our studios at NPR West. Thanks so much for coming to the program. Welcome.

Ms. AZAM ALI (Singer, Niyaz): Thank you so much for having us. It really is an honor to be here.

Mr. LOGA RAMIN TORKIAN (Singer, Niyaz): Yes, thank you so much for having us.

HANSEN: This is an interesting blend of modern electronica with a traditional folk song and sufi mysticism. Remind us briefly what Sufi mysticism is.

Mr. TORKIAN: Sufi mysticism came from Islamic tradition. It essentially developed in Iraq, about something around like 11th century.

Ms. ALI: If I may just add to that, one of the elements that's very appealing to us about Sufi poetry is that it does transcend cultural and religious specificity, because it really is more about the struggles of the human soul, the struggles of the human experience and something that we all share. It really is a universal struggle.

HANSEN: What does "Beni Beni" mean?

Ms. ALI: It means, to me, to me. "Beni Beni" is really about man struggling with his soul, and he's asking God, well, you put me in this world with all its beauty and yet all I want is to find my way back to you. So you have put me here, and you have not shown me how - how I can find this way back to you. So just please show me, give me some sign, show me how I can find my way back to you.

Mr. TORKIAN: And if I may add, you know, even today, in a lot of Sufi gatherings is always complemented by rhythm and dance. And in fact, the most revered Sufi poet, Rumi, composed his poetries most of the time to the rhythm of what was being played in the gathering along - when the dancers were dancing.

HANSEN: Loga, let me ask you, because the instrumentation on this album is really impressive. Some of the instruments, what are we hearing?

Mr. TORKIAN: For example, I used saws. Saws is a Turkish instrument. I used the lafta, which is also a Turkish instrument. Then from Iran I used the sitar, and also I have created a new instrument called kamman, which is - comes from the family of spike fiddles, and a lot of the bold or the legato sounds were created by that instrument. And then, you know, we've had Indian instruments, the bansuri, which is a flute instrument, tabla, which is a percussive instrument.

HANSEN: Azam, I understand you trained with a Persian master and you're an accomplished hammered-dulcimer player.

Ms. ALI: Yes. Thank you.

HANSEN: Well, this is an instrument that many know because of its use in American folk music. You know, it's essentially a stringed instrument, and you play it almost like a Marimba with four small covered sticks. Is there a difference in the playing or the instrument itself when you play this music on the hammered-dulcimer?

Ms. ALI: Well, the technique is very different, and you know, almost every part of the world has a different variation of this instrument. The Persian style of playing is very much - you know, we mute the mallet, which, you know, trying to get the sound more softer and almost - if you open a piano, it looks identical, you know, it has the muted mallets. So in Persian classical music they try to make it sound more like a piano, but I prefer the bit more folky, sort of rough sound, so I just play it with the stick side.

HANSEN: Let me read the English lyrics, too. Faraghi, the separation has caused me immense sorrow. Destiny has me chained to this state. O beloved, release me from these chains for I am bound with the dust in this estranged land. What is it you seek from me that you cast your chains upon a free man?

Ms. ALI: It's very, very easy talking about a physical exile of being far from your homeland, or is it just the exile of a soul being separated from its creator?

HANSEN: Both of you are Iranian and you now live in the United States. Azam, you were raised in India. Can you just tell us a little bit about yourself because on the cover of the album it looks like Los Angeles meets New Delhi meets Iran.

Ms. ALI: Yeah, well, you know, my mother sent me to India when I was four years old to study in an English boarding school, and then the Revolution happened, I was pretty much stuck in India. My mother was in Iran, and I didn't see her for a good six years. And then my mother escaped after, you know, during the Revolution, and she came to India. She lived there for two years. And when I was 15 years old, we came to the U.S. under political asylum because my mother didn't want to go back to Iran. So, you know, I've been here since 1985, you know, just trying to do the best that I can. It's been very challenging. I came during a difficult time, you know, soon after I was here, you know, Desert Storm. I mean, since I can remember, always, there is so much negative media around Iran and especially nowadays. It's virtually impossible to turn on the news and not hear something negative about Iran. And it's really a struggle for, I would say, every Iranian. You know, in many ways my life's work has become about this. You know, create something that hopefully transcends religion and culture and show people that, you know, at the core, we are all the same.

I tried so hard to just be American and just sort of almost reject my heritage. And it got to a point where I realized, you know, I'm never going to be 100 percent American. I'm never going to 100 percent fit in. So then I began to process within myself of sort of going back and learning about my own culture, embracing my culture. And once I did that, you know, I began to feel much more, sort of, whole. This music is an honest, honest manifestation of who we are as Iranian immigrants.

HANSEN: Azam Ali and her husband Loga Ramin Torkian are members of the ensemble, Niyaz. Their recording, "Nine Heavens," is available on Six Degrees Records. They spoke to us from our studio at NPR West. Thank you so much.

Ms. ALI: Thank you very much for having us.

Mr. TORKIAN: Yes, it's our honor to be here.

From: https://www.npr.org/transcripts/95607779

Daisy House - Leaving The Star Girl

Just stepped out the Tardis, back from a quick trip to San Francisco circa 1967 and I could swear I heard Daisy House blasting out of some greasy spoon on the Castro. They’re that authentic. Welcome to Daisy House. If you love Joni Mitchell, the Mamas and Papas, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, or Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, then you are going to want to stay awhile. I went to their bandcamp site to download just a few choice cuts but ended up buying it all – they’re that good. It’s not just that they emote a particularly addictive blend of 1960s folk rock and killer harmony vocals; the songwriting is also first class. Daisy House are a father and daughter duo, Doug and Tatiana Hammond, with dad writing and playing on nearly all the songs while both provide vocals. Over four albums, they have developed their clear influences into an impressive body of work.

The debut is simply 2013’s Daisy House. The basic formula is here: twelve string acoustic and electric guitars, a celtic twist in the songwriting, with vocals reminiscent of Joni Mitchell (on “Ready to Go” and “Cold Ships”), the Mamas and Papas (on “Two Sisters”), and Richard and Linda Thompson (on “The Bottle’s Red”). The Byrdsian influence is particularly strong with dad’s vocal on “Statue Maker.” 2014’s Beaus and Arrows reproduces the ambience of the debut, with a few new surprises, like a very early solo Paul Simon atmosphere on the Salinger-inspired “Raise the Roof Beam Carpenter.” I agree with Don over at I Don’t Hear a Single, the first two albums draw heavily on 1960s British and American folk idioms.

Things break out in new directions with 2016’s Western Man. There is an eerie mystery to the musical ambiance of the opening track, “Lilac Man,” that signals a significant stylistic shift. “Yellow Moon Road” expands the duo’s palette to include more 1960s garage rock sounds, particularly some cool organ. And the songs are amazing. “Like a Superman” has a clear Mamas and Papas stamp, “She Comes Running to Me” is lathered with great harmonies, while “Twenty One” opens with a deliberate homage to “When You Walk in the Room” before branching into its own original sound. But the album’s highlight is undoubtedly the hit single-worthy “The Boulevard.” You can just hear Mama Cass belting it out while the Wrecking Crew provides the crisp, swinging backdrop – except that it is not those amazing performers, it is these amazing performers: Daisy House.

This year’s Crossroads is another breakthrough for the duo, putting their sound more solidly on the rock side of folk rock. On “Languages” Tatiana sounds like a young Chrissie Hynde. This is the hit single, but there are many more highlights. The title track, “Crossroads,” has some Tom Petty Wildflowers-era bite while “Leaving the Star Girl” ramps up the Byrds influences. Dad is featured vocally on the evocative Paul Simon-esque, acoustic-based “Pristy Lee” and the more Byrdsian “The Girl Who Holds My Hand,” both strong songs and performances. But the highlights for me, beyond the obvious single (“Languages”), are two Tatiana vocals, the Kate Bush-like atmosphere on the beautiful and haunting vocal of “Albion” as well as the more Chrissie Hynde delivery of “Night of the Hunter.” Daisy House are a fully formed artistic wonder, inspired by the electric folk music and harmonies of the 1960s but entirely their own thing in terms of original material and performance. Visit them online, buy their music, see them live, now. From: https://poprockrecord.com/2017/06/28/welcome-to-daisy-house/

Children of the Sün - Sunchild

I am not a child of the 60's or 70's. I am, however, a child of a child of the 60's and 70's, and that has made all the difference in my current state of musical appreciation. Not to say the hippie aesthetic is my thing--far from it--but folk and proto-rock planted a certain something, and every once in a while, it's fun to revisit. Enter Flowers, the forthcoming debut LP from Sweden's Children of the Sun.

Sonically and thematically, Children of the Sun's brand seems, at first blush, easy to place. Vocal harmonies? Check. Liberal application of hammond-esque keys? Check. Pitter-pat percussion? Check. Airy acoustics? Check. Back-to-the-earth sentimentalism? Double check. Take your favorite carefree folk rock--Traffic or perhaps Blind Faith as several examples among many--and mix, sparingly, with the modern edge and vocal prowess of MaidaVale or Halos and Hurricanes-era Avatarium. The latter may be a stretch, but Josefina Berglund Ekholm and Jennie-Ann Smith certainly share similarities in syrupy-yet-grounded delivery.

Why “first blush,” however? As it turns out, the acoustic intro and the hooky highlight “Her Game” are but a fraction of the unique genre stew offered across the breadth of the Flowerpatch. Take “Hard Working Man” as a prime example, which feels more out of the Dixie Chick's country-pop playbook than anything (and this, I hasten to add, is far from an insult.) And then we've got the intriguing “Like the Sound,” which sounds like Church of the Cosmic Skull with a dangerous case of confident vocal gravitas. The swell and fall of Josefina's croon on this track is haunting--dare I say goosebump inducing--and cements it as the album's standout track. This presents a thin margin, however, as the choral “Emmy” as well as the aforementioned “Hard Working Man” and “Her Game” are absolutely brilliant tracks as well. Like the best of their feather-in-the-hair influences, these tracks have meaty hooks, standing on the merit of massive songwriting chops, rather than an established ambiance.

Critically, there are two aspects that stand out after repeat listens. Firstly, the variety, while an obvious strong suit, means that some distinct instrumentation is employed once, and thus feels more like an outlet than a piece of the album's fabric. I'd love, for example, to hear more of that twangy guitar, for example, but the other tracks are so unique in their identity that there really is no room. Eclecticism is a strength, but it's a fine line between “establishing individuality” and “sabotaging the bond that holds the album together.” That said, am easy solution next time around is simply throwing in a few more tracks--at 35-ish minutes, there's room to play.

I've gone back and forth on my justification of Flowers’ inclusion in the Village annals...because it obviously made the cut, albeit not on the merits of an intrinsically heavy nature. Rather, Children of the Sun appears herein because the traditional from which they are born informs, on many levels, what we listen to on a regular basis. And that's not to mention the sheer strength of the songwriting and their technical chops, which certainly deserve recognition. If you typically dwell under the umbrella of the heavy, aggressive, and loud, this album may not be your cup of tea--and I get it. But if you don't mind taking basking in a grassy meadow from time to time, give Children of the Sun a well-deserved chance. I think you'll be pleasantly surprised. From: https://www.sleepingvillagereviews.com/olde-reviews/children-of-the-sun-flowers

Antiprisma - Um Minuto Desse Ano

Antiprisma is a band that has been standing out on the Brazilian indie scene for a few years now. The striking folk sound of the duo formed by Victor José and Elisa Moreira has been gaining ground since the band's first self-titled EP, released in 2014. After that, the first full album, Planos Para Esta Encarnação, already showed the greater possibilities that the two were able to create based on their vocal melodies, their guitars and Victor's interventions on the caipira viola, played in a very unique and interesting way. For 2019, the band decided to shake up its sonic possibilities and brought four singles throughout the year which, last Friday, joined together with six other songs to form Hemisférios, Antiprisma's second album. Guitars, bass and drums accompany Victor and Elisa through tracks that, even though they bring a new approach to the band's proposal, still show their essence and identity. To better understand the paths that led Antiprisma to reach Hemisférios, we chatted with the band via email, and you can check out this conversation here:

TMDQA: Firstly, I would like to know about the launch process for Hemispheres. Before the full album even came out, you already released four singles that would become part of it, why did you decide to show so much about what this new work would be about in advance?

Victor: Firstly because it had been a while since we released music. Furthermore, we noticed this tendency to emphasize more on working single by single, so we wanted to try this idea, as some tracks were ready a little earlier. There's also a bit of a curiosity factor, right... we wanted to know at least how these new songs might sound from other people's perspectives. We spent so much time on the project that releasing these songs earlier was a bit of a relief, you know? As we were already thinking about releasing 11 or 12 tracks, we thought it would be reasonable to release four songs in advance, because when the full album was released there would still be a lot of material to listen to.

Elisa: I think the singles are tracks that exemplify the new paths we followed on the album, and the most current look of Antiprisma. The launches served to keep the "wheels spinning" (laughs). I think we managed to release new things and still bring other new sounds to the album. Furthermore, in fact the tracks that were released as singles are part of a whole, and may even gain a different perception within the context of the album.

TMDQA: Still about these singles: "Fogo Mais Fogo", "Só Causa Você Não Se Encontrou", "Caos" and "Planície Sem Nome". Why were these the tracks chosen to preview the album? And how do you believe they were able to translate the idea of Hemispheres to those who were waiting for it?

Victor: For me, there are other tracks on the album that could have come out as singles before, but these four tracks in a way sum up what's recorded there. I think I see in them the paths we ended up taking. It has a bit of calm and harmony as well as a more aggressive and incisive streak.

Elisa: We chose "Just Because You Didn't Meet" because we noticed a good reception when we played it in shows, still as a duo. We noticed that people paid attention to the song itself and the lyrics, which have a strong message. "Planície Sem Nome" we noticed right away that it would have potential as a single, as it has a more pop melody. "Caos" would bring folk and acoustic, which are important elements of our identity, but with a darker approach, a different mood than what we had presented before. And we decided to open everything with "Fogo Mais Fogo", which immediately brought a vibe that would break with the expectation of an acoustic, calm Antiprisma release... this track is very strong and features Gabi (Gabriela Deptulski, from My Magical Glowing Lens ) took a more psychedelic approach. We think it's a good milestone to start our new phase.

TMDQA: Now about the album as a whole. Anyone who follows Antiprisma already knew that the band was accompanied by more musicians in their performances, and you could already imagine that this would also be seen in the final result of Hemisférios. How did this accession of new members happen and how did it impact the new work?

Victor: We simply realized one day that maybe it was time to try playing with a full band, with a conventional lineup. You see, although from the beginning we followed this acoustic vibe, based more on vocal harmonies, it was never our intention to continue like this forever. We kind of knew that this aspect would always be present in anything we did, but we also knew that at some point this moment would come to play with a band. Sometimes we need to play a guitar, and a kitchen with bass and drums opens up another world for us to explore. It has been very good and very interesting to maintain both formats, duo and quartet, the music benefits a lot from this.

Elisa: When we started recording this album, we already had the idea of playing live with a full band, but we hadn't yet finalized a lineup. So, on the album we recorded ourselves, and invited our friend Marlon Marinho to do the drums. Our idea live is not to literally reproduce what is on the record - although it doesn't deviate much from what is there -, but to transmit our "vibe", which is on the record, in a less introspective way than as a duo.

TMDQA: Something very curious about this new album is the presence of more intensely instrumental tracks, with some even entirely without vocals. What was it like composing these songs and how did the decision to include them in Hemisférios come about?

Elisa: All of our strongest references have important instrumental moments, so for us it was a natural decision.

Victor: Recording instrumental things has always been a great desire. For Hemisférios we separated two tracks like this, "Lunação" and "Cenário" . The first is a composition that came from Elisa, we broke down the whole thing and in the end it had this post punk feel. We even embraced the idea of using a Cocteau Twins sample to make the beat. This was one of the ones I most enjoyed doing. "Cenário" came from a riff I made on the viola and that ended up taking on an interesting look; I think it turned into an emotional sound, and it was a great addition to the album's tracklist. Despite paying a lot of attention to the lyrics, in general the instrumental on this album was very rich. It has many moods in it.

TMDQA: And finally, how is the band feeling about leaving their comfort zone, experimenting with other sounds and now playing with electric instruments and other members in their performances? Tell us about this experience that the new album is providing for you.

Elisa: We felt this desire to try a full band, but we ourselves didn't really know how we would sound... One concern we had was to arrive at a sound that didn't "swallow" the personality of either of us, that maintained the balance that we always strive for - we are a girl and a guy playing and composing, side by side, in equality. And that for us reflects in our sound. One of the fears about playing with a band was that it could "unbalance" the sound, for example leaning too much towards Victor's references, sounding more masculine, or towards mine. Look at the girls (laughs) We did some shows with different lineups until life made us bump into Ana and Rafa, who are currently doing our "kitchen" live. Together with them, we are increasingly polished in our band version, discovering and creating our electric face for live shows

Victor: This entire period of composition, recording and rehearsals has been Antiprisma's most intense. Honestly, it's a great relief to be able to create in other ways, express yourself in other ways. We feel very comfortable at Antiprisma, and I think that although we have changed a lot in some aspects, our style is definitely there. And even though it's different, there's a good part of the album that has the feel of the EP or Planos Para Esta Encarnação. I think this new job has given us even more of an ability to see other things about ourselves from a different perspective, and it's really crazy that playing live with this electric approach makes it feel like a "fresh start" for us.

From: https://www-tenhomaisdiscosqueamigos-com.translate.goog/2019/09/03/antiprisma-entrevista-hemisferios/?_x_tr_sl=pt&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

Monday, July 22, 2024

Morphine - Live at The Westbeth Theater 1997

During the first weeks of 1993, Pixies frontman Black Francis unceremoniously ended his band via fax, leaving the mantle of Massachusetts’s most beloved college band temporarily vacant. The Kim Deal-led Breeders were logical successors, but the scene had a fairly stacked roster with Buffalo Tom, The Lemonheads, and Dinosaur Jr. all releasing new material that year. Meanwhile, a steely-eyed, magnetic prophet emerged from Cambridge with a homemade two-string bass and one of the area’s most singular bands behind him.

That year, Boston-based band Morphine perfected a precise formula of jazz-informed cool and bluesy punk to briefly inspire an international fervor. The band mournfully concluded with 2000’s “The Night” a year after frontman Mark Sandman’s sudden passing mid-performance, but their nocturnal sound arguably solidified with 1993’s “Cure For Pain.” For the local crowd, “Pain” was more than a hometown hit; it embodied a Boston nightlife that critics and outsiders didn’t believe existed. It was as unbridled as a collision of bodies at The Model around last call, as introspective as a long walk home across the Mass Ave. Bridge after midnight, yet “Pain” was completely untethered from any other sound in the scene at the time.

“That was the best batch of songs Mark Sandman wrote for a record,” producer Paul Q. Kolderie says. “He was just really on fire right around then; every song that came out was another winner.” “'Cure For Pain' just loudly announces that it is a classic,” author and Hallelujah the Hills frontman Ryan H. Walsh adds. “It doesn’t lean into any of the things about the ‘90s that stand out and say, ‘oh, this is from the ‘90s.’ The production and the very structure of the band itself kind of flew in the face of what was popular and cool or trendy.” As far as its creators are concerned, the era surrounding Pain was one of triumph, loss, fatigue, and a continued effort to be effortlessly in the moment.

Colley, Sandman, and drummer Jerome Deupree began playing as Morphine in 1989, but the group’s unorthodox sound had roots long before they got together. “We were all really old friends,” Kolderie says. “By the time we got to “Cure For Pain,” we had already made one record together and I had made numerous records with all the people involved.” Morphine’s tangled web of scene friendships began in the early ‘80s with The Sex-Execs, a cheeky new wave act featuring Deupree on drums and Kolderie on bass. Colley was playing saxophone in the more subtly-named Three Colors, which Kolderie produced an album for before they split in 1988. Out of all of their priors though, Sandman’s Treat Her Right had the most promise, simultaneously foreshadowing Morphine’s sound to come.

“Mark had nine lives, so when he first got to Boston, it took him a while to find his footing,” Kolderie says. “When he fell in with the Treat Her Right people, that voice was there all of a sudden.” With a driving blues sound highlighted by Sandman’s “low guitar” bass style and lyrics pulled from his vagabonding across North and South America, Treat Her Right released three albums and scored a deal with RCA Records before disbanding on the heels of Morphine’s debut, “Good” in 1992. “Back then, we were all just striving,” Kolderie adds. “We were all just trying to come up. We made a previous record that was good, literally called “Good,” but I think we were determined to beat it.”

Production on “Cure for Pain” was spread over a brief two weeks at Kolderie’s revered Fort Apache Studio in Cambridge, but days into recording, Morphine’s lineup experienced a shake-up. According to Kolderie, Deupree quit because of tension with Sandman coupled with some health issues keeping him from extensive touring. Deupree says he saw the recording as a “favor” to record a demo tape of the songs they’d been working on. Recording was happening at such an expedited clip, Deupree’s replacement, ex-Treat Her Right drummer Billy Conway, would only have to play on three songs for the record. Whether it was their focus or confidence as a trio, “Pain” had already began generating hype before basic tracks were even finished. Kolderie’s girlfriend, then a publicist for Warner Music subsidiary Rykodisc, took a cassette of unfinished mixes to the label after overhearing Paul working on the record. Rykodisc signed Morphine on the strength of the cassette, going as far as to reissue “Good” ahead of “Pain.” “We went to another studio called Q Division,” Kolderie adds. “I put on the tape, started playing ‘Buena’, and people were running into the control room like, ‘What the fuck is that?’ You notice when these things happen.”

Morphine’s slow rise was both word-of-mouth and a product of the band’s constant tinkering sonically. Sandman’s storytelling had become more direct in the year since “Good,” revealing vivid accounts of adultery (“Thursday”), strung-out vices (“Cure For Pain”), and self-doubt (“I’m Free Now”). Colley had mastered a kind of sax showmanship that anchored a song’s melody while flashily playing two saxophones at once live. In the shift from Deupree to Conway, Morphine had been blessed with two drummers that had years of experience playing off of Sandman and Colley. “I’m very proud to be a part of it,” Deupree says. “If people know me as a drummer outside of Boston, it’s because of 'Cure for Pain.'” As much as the album stands as a group effort, some of its most resonant moments come from the insular recordings from Hi-n-Dry, Sandman’s Cambridge loft/studio.

With a seemingly endless array of anonymous lineups and musicians coming by to pitch in, Sandman’s private output was a precursor to the eclectic lo-fi producers of the Bandcamp age, hitting record as soon as inspiration struck. The record’s atmospheric album closer, “Miles Davis’ Funeral,” simply came about when Sandman and percussionist Ken Winokur were rolling tape on the day of the jazz icon’s burial. More fully-formed loft experiments like the crystalline, mandolin-plucked centerpiece “In Spite of Me” ultimately inspired Kolderie’s self-described “let’s fucking do this” attitude in the studio. “We were just trying wild things,” Kolderie adds. “There was one mix of ‘A Head With Wings’ where I had the sax track routed to a wah-wah pedal underneath the console and I was literally playing the wah-wah pedal live while we were mixing the song. I don’t think I did that with anyone else.”

“Cure For Pain” was released on September 14, 1993, kicking off an expansive tour across the globe. The album received an early cosign in the form of multiple songs being featured in director David O. Russell controversial 1994 hit “Spanking the Monkey.” Fittingly though, Morphine picked up the most steam from late-night television appearances, entertaining Conan O’Brien, Jools Holland, and, most notably, Beavis & Butthead. “It seemed to snowball and it was worldwide,” Colley says. “We were working a lot, so we never got a chance to just stop and take inventory. We were on the road, like, nine months of the year traveling around the world, going from one place to the next, and just repeating it.”

Despite their globetrotting successes, Morphine kept a fairly low profile once they eventually returned to Boston, earning a restrained sort of respect from locals that seemed to suit the reserved band. “That’s why I loved to come back to Boston: it didn’t change,” Colley adds. You saw your friends, they were like, ‘where have you been for the last couple weeks?’, ‘oh, well, we were on tour,’ ‘oh, welcome back.’ Nothing changes, nobody looks at you differently, and you could slip right back into playing little bars with your friends.” “There’s nothing that I loathe more than rock stars who are big time people when they’re talking to me. To find he was the antithesis of that was such an awesome addition to his talent,” Walsh says about his brief encounter with Sandman in the ‘90s. “He was easy to talk to, but clearly, he also cultivated a mysterious aura around him. That shit wasn’t accidental.”

Even before Mark Sandman’s fatal heart attack while headlining the Nel Nome Del Rock Festival in 1999, Morphine’s future, to some, was in question. Pain’s follow-up, 1995’s “Yes,” doubled down on its predecessor’s winning formula of romping live hits and Sandman’s nocturnal observations, but 1997’s “Like Swimming” brought additional pressures to the band. Morphine had signed to nascent major label Dreamworks Records, which seemed to bolster the anticipation surrounding “Swimming” while baiting critics that had doubts about the group. “They desperately need to alter their sound, and if they have to break up to do it, I don't think anyone's gonna care,” Pitchfork founder Ryan Schreiber wrote in a scathing, since-deleted review. “In fact, after four identical records, it's about time, 'cause Morphine is, like, drowning.” “I think they (the band) found the sound and, if there were problems with any of the later records, it was just because there was this profound conflict between sticking to the sound they had or trying to go somewhere else,” Kolderie believes.

In the decades following the band’s tragic dissolution, the surviving members of Morphine have managed to find a happy medium between “sticking to the sound” and expanding somewhere else, thanks in part to New Orleans-based blues musician Jeremy Lyons, who says he initially listened to “Pain” upon meeting Colley and Deupree to a point of exhaustion. “I think I actually remember getting to a point where I couldn’t listen to it for a while because it was very sad, some of the songs, whereas I think the follow-up is a bit more rock and I felt some of the tunes had a bit more of a party feel.” After casually jamming for years, Colley floated the idea of performing a “members of Morphine” set at Nel Nome Del Rock in 2009, just one day shy of a decade since Sandman’s passing at the same festival. The passionate tribute performance led to a residency at Atwood’s Tavern back in Cambridge and marked interest across the States for reunion shows. “I really had to relearn how to sing in order to do the Sandman stuff,” Lyons says. “His range is naturally lower than mine, but he also had a beautiful way of singing very gently and quietly.”

The topic of a “Pain” anniversary was brought up and tabled over the years as Vapors of Morphine became a project with as much longevity as the original Morphine. This past February, a 25th anniversary performance of “Pain” front-to-back at the Lizard Lounge was met with a sold-out crowd and a second set to keep up with demand. “For us, it’s been great to reach out and to have that next generation come up to us and say, ‘my dad played Morphine in the car when I was going to preschool’ or ‘my mother used to put headphones on her belly when she was pregnant with me and played you… now here I am with a full beard, let me buy you a drink,’” Colley says with a laugh.

The record’s endurance goes far beyond nostalgia though; as much as it was a part-realized, part-idealized vision of Boston’s nightlife, the record has since become an underrated document to its younger fans of adulthood, warts and all, while trying to grasp at fleeting youth. “To me, it was like a glimpse into adult life,” Walsh says. “It was a very unique kind of adult life and not an entirely happy one, obviously. It wasn’t pop fluff, it was short stories about the difficulties of being an adult.” Regardless of the album’s contained, but enduring legacy, Colley, Deupree, and Lyons will carry on, playing the songs they’ve been growing and tinkering with for over 25 years. As far as new fans coming aboard, Colley is confident that he’ll keep getting requests to play “Buena” as long as they’re playing shows. “I think if you’re interested in music, you’re going to find your way to Morphine eventually,” he says with a calming degree of certainty. From: https://www.wbur.org/news/2018/09/14/morphine-boston-band-cure-for-pain

The Heavy Heavy - All My Dreams

One of the hardest parts in this job is nailing a comparison. Artists groan when their work is pitched against someone else’s, no matter if it’s right on the money; journalists, meanwhile, quake at the idea of making one in fear it’ll blow up in their face and feature as the key storyline in the artist’s next press campaign… been there! Best, then, to push the artist to do it themselves, and not let them weasel out of it with a “we like a bit of everything” before they curate an ill-fitting ‘influences’ playlist for Spotify. The Heavy Heavy, thankfully, have no qualms over comparing their sound and their work to their heroes. Their answers? The Rolling Stones and The Mamas & The Papas. “The Stones are the bottom of everything we do,” Will Turner, one half of the Brighton duo, keenly tells NME of the key influences behind ‘Life and Life Only’, the band’s debut EP that’ll be released on vinyl this week (July 22).

“One of the main goals for us is to make people feel good,” adds vocalist and songwriter Georgie Fuller. “And there’s so much music out there that’s sad, but The Rolling Stones have this magical quality to make you feel good and feel like life’s a party. And The Mamas & The Papas had the glistening West Coast sound that we love, too.” It’s this attitude that makes ‘Life and Life Only’ such a refreshing listen. This is folk-rock that unashamedly harks back to what Turner calls his favourite period of music: lush ‘60s pop through to the early ‘70s, and the birth of the digital era. In the wrong hands, this refined mindset would sound crusty, snobby and tiresome, but here that approach generates songs that are familiar, accessible and rather quite exciting.

“We’re not trying to create a pastiche or make another sound that’s identical to something that exists, but to carry on what we believe is the greatest era of music,” Fuller says. Michael Kiwanuka, Leon Bridges and Paolo Nutini are such acts who, like them, aren’t repeating history, but instead taking their inspiration from it, and they sound like some of the “coolest records ever” Turner is more blatant: “There was a similar set of ingredients in that 10-year period that I think was the best sound ever, whether that was Joe Cocker, The Beatles or Led Zeppelin. We want to try and exact those ingredients and put them in every song that we do. Aim for Aretha Franklin, going for Bob Dylan… we want to go that high. I don’t think there’s any reason to settle for anything less than the ‘best ever’.”

‘Go Down River’, the first song the pair worked on together, is a rich soul ballad that acts as the midway point of The Band, Otis Redding and Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson. ‘All My Dreams’, a funk-rock groover, has hints of Steppenwolf and Janis Joplin, and the harmonies on ‘Man Of The Hills’ appear plucked directly from The Mamas & The Papas’ ‘Dedicated To The One I Love’. It’s a sound Turner has been chasing for over a decade. His previous band fizzled out, but a chance appearance from Fuller on one of their tracks opened their mind to a new way of working. “Something about the way my voice hit the mic and the way he produces the sound, we had a moment where we were like, ‘Woah!’” Fuller says.

In little over two-and-a-half years, the pair have released their debut EP, expanded to a five-piece band and signed to ATO Records, home to Nilüfer Yanya, Alabama Shakes and Black Pumas. Things appear to be accelerating: not only did they recently appear on CBS’ Saturday Morning TV show for a live performance of their Americana-tinged single ‘Miles & Miles’, but they also just completed a support slot on labelmates Black Pumas’ European tour. It was, incredibly, the band’s first-ever full tour and saw them playing to growing venues across the continent. They’re grateful that the psych-soul band’s fans got down early for their set and made up for lost time by snapping up their merch. “They’d buy it, put the t-shirt on and then stick out their bellies, and we’d sign the tops for these slightly rotund German men,” Turner laughs.

Aside from the merch takings, valuable lessons were learned. They were in awe of Black Pumas frontman Eric Burton’s magnetic stage presence, and geeked out with guitarist and producer Adrian Quesada on sound technique: it’s the kind of advice they’ll use when stitching together their debut album later this year, for which they have 40 to 50 demos. Most of all, it set a new benchmark, and another chance to follow in the footsteps of those they consider the best. “Watching them up close and realising how they got to this level was a huge eye-opener,” Fuller says. “It made us think, ‘Fuck, if we work hard like they do, this might be possible for us.’” From: https://www.highroadtouring.com/the-heavy-heavy-our-sound-the-rolling-stones-meets-the-mamas-the-papas/

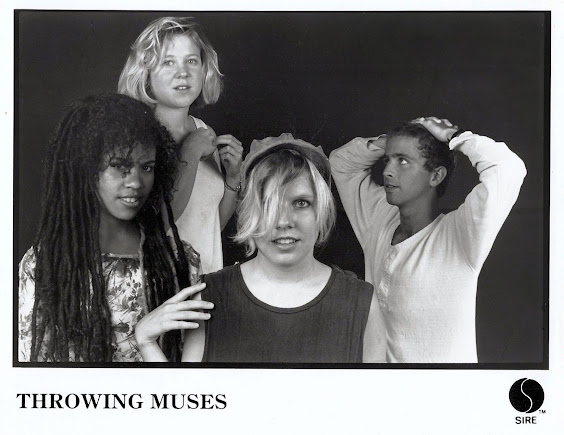

Throwing Muses - Sunray Venus

The debut album by Throwing Muses was released in 1986, at the beginning of my sophomore year of college. Back then I had a friend who listened almost exclusively to artists on the British independent label 4AD, and I wanted to have musical tastes as esoteric as his. He told me that Throwing Muses—who lived in Boston, like we did—was the label’s first American signing, and I bought their record without having heard a note of it, only moments after a clerk in the Harvard Square branch of Newbury Comics slipped it into the “new releases” bin. I reasoned that since the record had come from England, and Boston was the easternmost major port in the United States, I was probably the first person in America to buy it, and for a long time I went around saying this. At that time my friends and I played a lot of I-heard-them-before-you-did—I saw R.E.M. in a tiny club with only fifteen other people before they were famous—and naturally there was a little of this involved, but my proprietary feelings toward Throwing Muses were more personal. I had finally found the music that was meant for me. Back in my dorm room I studied the inner sleeve of the record trying to make sense of the lyrics. Sometimes an obvious meaning broke through. “Home is a rage, feels like a cage”: I understood that. But even when coherence was just out of reach, the music completed the logic of the songs. I heard the anguish and frustration in Kristin Hersh’s thin, quavering voice. The instruments churned and chugged, or mapped out herky-jerky rhythms, and frequently broke into a wild, cathartic hillbilly dance.

He won’t ride in cars anymore

It reminds him of blowjobs

That he’s a queer

And his eyes and his hair

Stuck to the roof over the wheel

Like a pigeon on a tire goes around

And circles over circles.

I had never before heard a song with the words queer and blowjob in it. But I had just come out of the closet, and this song, “Vicky’s Box,” somehow made me feel acknowledged. The wheel and the pigeon were mysterious, but they felt true. It was as though the band had detected the dark, metallic sadness that I was so urgently trying to believe wasn’t there. “Kristin puts a lot of pictures in front of you, and you draw your own conclusions about how they all fit together,” David Narcizo, the drummer for Throwing Muses, tells me during a recent Skype conversation. “You also don’t have to if you don’t want to. I used to liken it to early R.E.M. and Cocteau Twins. I didn’t know what they were saying, but there are moments in those songs when I would think, I totally feel that. You get a sense of something genuine, but you don’t have to define it.”

Hersh formed Throwing Muses in the early 1980s with her stepsister, Tanya Donelly, while they were teenagers growing up on Aquidneck Island on the Rhode Island coast. Both played guitar and sang; in the DNA of Hersh’s early songs you can detect traces of such inventive and intuitive punk bands as the Raincoats and X. The sisters recruited Narcizo, a childhood friend, to play drums, and Leslie Langston, a local musician, to play bass. Hersh was the primary songwriter; Donelly contributed one or two songs per album.

An impressionistic timeline:

1987: Throwing Muses play a surprise Saturday afternoon show at the Rat, a grubby basement club, and I watch while standing on a chair at the side of the room. The ceiling is so low that I can touch it. The band performs a few new songs, and this is when I first hear Hersh’s “Cry Baby Cry,” a clarion call against despair that still has the power to remind me of why it’s good to be alive. The room swells with sound, and for a moment I have the exhilarating sense that I’m actually inside the music. “The whole point of doing a show is to turn a room into a church,” Hersh says twenty-six years later when I interview her by telephone, and I remember how that concert gave me a feeling of transcendence that I had never felt inside a real church.

1988: At Newbury Comics (I lived at Newbury Comics), a bossy friend whose every word I hang upon sees me pick up House Tornado, the band’s new, second album, and says, “You’re not going to buy that, are you?” I sheepishly let it fall back. I’ve started frequenting Boston’s dance clubs, and my friends and I are fans of arch and polished British bands like Pet Shop Boys and New Order. It takes me a while to learn that I don’t have to take sides.

1991: I read a glowing review of a new Throwing Muses album, The Real Ramona, and regret that I ever turned my back on them. I buy all the albums that came out while I wasn’t listening.

1992: Donelly begins writing more songs and leaves to form Belly, her own band, which includes two brothers with handsome surfer looks. I so eagerly await the appearance of their first album that on the night before its release I have a dream that one of the brothers asks me to be his date to the launch party. Meanwhile, Throwing Muses regroups as a three-piece, with new bassist Bernard Georges.

1994: Hersh’s first solo album, Hips and Makers, appears. Her songs have by now taken on a yearning sweetness. Nonetheless, when I play the single “Your Ghost,” for my guitar teacher, because I want him to teach me the fingering, he has difficulty figuring out the time signature. “Who’s that singing with her?” he asks me. “Michael Stipe,” I reply. “Oh,” he says, “well, no wonder.”

1996: I pretend I am sick, employing some dramatic fake coughing, so that I can leave work early and buy a Throwing Muses album called Limbo on the day of its release at an HMV in midtown New York that is now a Build-A-Bear Workshop. (And maybe, since it’s barely lunchtime, I am once again the first person in America to buy it.) Not long after, the band leaves behind the world of corporate rock. Living in different parts of the country, they tour and record together less frequently—their next album doesn’t appear until 2003.

2011: Hersh, an early adopter of the pay-what-you-wish model, posts solo demos for a new Throwing Muses project on the CASH Music Web site. I am immediately convinced that they are among the best songs she’s written.

Purgatory/Paradise—the band’s first album in ten years—comes with a downloadable commentary track during which Hersh and Narcizo chat about the music while it plays in the background. There’s a heartbreaking song called “Dripping Trees.” “You a clean spark or a twisted parody? Well, look at me,” Hersh sings. “These wicked memories—it all comes down, eventually.” The melody sounds like something tumbling earthward, in slow, sad, stately spirals, and yet still landing perfectly on its feet. “This is such an ‘us’ song,” she says on the commentary, and laughs. “It’s so us because you can’t tell if it’s saying something good or something bad … Anthemic and pathetic at the same time.”

From: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/12/17/jewel-toned-insides-talking-with-throwing-muses-and-tanya-donelly/

Uni and The Urchins - What's The Problem

Charlotte Kemp Muhl, Jack James Busa and David Strange form the core of Uni and the Urchins, a band that is beginning to rise out of a sea of possibilities to stake their claim as the newest concert stage superheroes. Having what it takes — vision, charisma and musical chops — the combo has taken an eclectic set of influences and poured it all into their first disc: “Simulator,” now out on Chimera Records. Chatting with them in their Downtown rehearsal/recording space yielded answers to some questions and raised a bunch more. For the record, Muhl — songwriter, film director, musician, model — explained the group’s origin.

“I went on Craigslist to find a mechanic to help me build a time machine and met David,” she recounts. “Turns out he didn’t really know how to fold time-space with a microwave and a Dell computer, but he was pretty good at guitar. Then Jack crash landed in my backyard like a flaming isopod and we kept him in the basement with canned food and a CRT (cathode ray tube) TV until he suddenly started singing.” Though their beginnings were humble, Muhl has some, well, let’s call them out-of-this-world ambitions for the project. “I’m hoping that we will get hired to be the elevator band for Bilderberg meetings. Maybe we’ll even get to play children’s birthday parties on Mars for the Illuminati. I’m currently speaking to the Chinese government about funding our performance of Moonlight Sonata on the moon,” she states.

Check out the videos for all of the tracks for a taste of Uni beyond the music, all of which were directed by Muhl. The stage show, recently experienced at the House of Yes in Brooklyn, includes surreal imagery and occasionally additional performers such as human blockhead Anna Monoxide. “I’d love to make the live show as spectacular as possible,” says Busa, the lead singer. “We’re so inspired by iconic tours that act more as theatre than a rock show, a la Bowie’s ‘Diamond Dogs’ tour, Madonna’s ‘Blonde Ambition,’ or pretty much anything Grace Jones has done. The live show should feel like a physical manifestation of the music and videos.” Some dissension crept in from Muhl, who responded, “Oh no. We’re very against theatrics. Only gritty realism for us. Only when you bore the audience can you get them to think deep thoughts.”

Thinking it best to let them work that out among themselves, we moved on to the topic of their accompanying visuals, which also includes their stunning outfits. Muhl explained the present state of their artistic evolution, saying, “We’re media polygamists, currently working our way up to crayons and macaroni art paired with interpretive dance” and Busa further noted that “the visuals are an extension of the music but also we’re very inspired by fashion and cinema and performance art so of course that bleeds into every thing we do.” Strange adds that, “I think we come from a very experimental place. We’ve never really let genres dictate where we go. It’s all about what serves the song.”

Their songs can be haphazardly described as a blend of glitter, punk, prog-rock, psychedelia, grunge and a few other things into what they call “neuro-divergent pop.” “I just call it art-rock,” says Strange. “We’re taking pieces of music from the history of popular music over the last 75 years and introducing them into new forms rather than reinventing the wheel.” Busa feels that he’s “generally pretty flattered by what people perceive our influences to be. Our fans are so smart and love all the nerdy references that we like.”

Watching all the videos one gets the idea that Muhl generates more ideas that she can use, which she confirms while giving us some valuable insight into her working process: “It’s true that I have too many ideas to sudoku, let alone Jack always wanting to be crucified and have alien backup dancers and David’s suggestions to have more necks on his guitars. So usually we just take a Kubrick film, play it backwards, project it onto a mural of Marc Bolan, film that with VHS, rub glitter all over the magnetic tape and overlay it onto a Cronenberg student film.”

One of the themes that crawls out of these productions is the concept of beauty, on which Busa muses, “I’m always attracted to anything that makes you do a double take, so to speak. Anything that makes you second guess what you’re looking at. We’re not trying to redefine anything but rather to look at the normal world abnormally.” “It’s weird,” adds Muhl. “I thought the praying mantis arms would get us another Maybelline deal for sure.” What do they want people to take away from their encounter with Uni? “Hopefully, not a rash,” says the ever optimistic Muhl. “I want people to be challenged and realize that there’s more out there beyond their four walls,” says Strange. “After an experience with Uni and the urchins, I highly suggest reaching out to a psychologist,” Busa replies. From: https://www.amny.com/news/downtown-glam-rock-uni-and-the-urchins/

Rasputina - Transylvanian Concubine

Rasputina is one of the most unusual and perplexing musical outfits of the past several years, successfully merging various elements of rock, pop, and classical music into their own unique sound. The band consists of Melora Creager, Julia Kent, and Agnieszka Rybska, three cellists who perform wearing turn of the century underwear. Your first reaction might be that this is a gimmick, but upon closer observation it becomes obvious that Rasputina is a band with an incredible amount of substance and style. Instead of writing songs that are easily understood and obvious, Melora Creager (the songwriter) chooses obtuse, off-the-wall ideas for her tunes. Songs like "My Little Shirtwaist," "Nozzle," "Transylvanian Concubine," "Howard Hughes," and "Rusty the Skatemaker" can't be easily categorized or understood. Lyrically Melora challenges herself and the listener constantly, with remarkable results. This telephone interview took place on February 28, 1997. Melora, now 30 years old, was born in Kansas City and now lives in New York. She has one brother and one sister. Her father was an administrator and a physicist at a university, and her mom was a graphic designer. Both parents were very supportive of the arts.

Do you do the graphics on your web site?

Yeah. That's one of the major fun parts of doing this for me, you know, to get to do the cover art and things like that.

What inspires you to write songs, Melora?

I would say mostly reading because anything that gets my imagination going then I really wanna, you know, with the song lyrics express something in a pretty small space... and I like to read a lot of history. I don't read a lot of fiction I think because that's somebody else's imagination and I prefer to, you know, get going on something else.

What other interests or hobbies do you have outside of music?

I was a jewelry designer for a long time while doing this for a living. I am driven to make things all the time, whether it's something having to do with my hands. Playing the cello is very hand-oriented, you know, also... which is kind of tactile.

How long have you been playing the cello?

Since I was 9. I think Julia was 6 when she started. Agnieszka was 9 also.

Do you consider yourself basically happy or unhappy?

Maybe I'm manic depressive because I'm a big mood swing person. Really high or really low. An extremist.

Have you always been like that?

Yeah. Melodramatic or something.

What's the difference between right and wrong?

I think everyone always knows inside the difference between right and wrong but it's hard to act on it. If you don't have that feeling inside, then you're a psychopath.

Do you think all people are created equal?

No. I think that between genetics, astrology, eugenics... between all the crazy components of people, there's a lot of combinations.

You are the first musician to answer "no" to that question.

Really? That's really surprising. Maybe people think that's the nice thing to say or good thing to say that they are.

Do you think people are inherently good or evil?

I think people are inherently lazy, which is harder to overcome. You know, to act out your ideas and to work hard on things... I think that's really hard. Probably most people want to do that and don't necessarily do it.

You've put a lot of energy and thought into Rasputina.

Yeah. We have a really strong general work ethic because it takes a lot of work just to be sounding good on the cello, you know. It's not an easy instrument. We enjoy it to torture ourselves and overwork.

Do you think success generally affects people in a positive or a negative way?

I think it's a pretty negative thing. I think trying to recapture success, when somebody is trying to write another hit song, I think that's pretty destructive and hard to avoid because it means repeating. Like, "How did I do so well before? I'd better do that same thing again." Bands as well become that way.

Do you think that harms people's creativity?

Yeah, yeah... I think it's a lot of pressure. Probably most performers have an intense need to be liked in a simple way and that can lead you to make not so good work, maybe. I deal with all that stuff too.

You ladies are getting a lot of attention...

Yeah, and even at this level it's a funny feeling because we've done this for awhile. As it becomes more public and we really have to think about "Why do we do this?" and "Let's not stress the underwear aspect."

Because you start thinking of yourselves as a marketable entity?

Yeah. I like to make an image or make characters out of us to some degree and to work with those kind of ideas but we're very earnest, with good intentions of expressing ourselves artistically and yet we're goofy so... What to make light of and what not is sometimes hard to decide. The biggest surprise to me is that it seems like the main thing about us to other people is that we're unusual, or they haven't heard it before. And it seems like there sure should be a lot more unusual things... It seems too easy to be unusual, you know.

I certainly agree with that. The critics are behind you, but I can't help but think that your music is way over the heads of most music buyers.

I tend to think that general audience people... that there's a few people of every different type that would really understand it and like it, you know, that it's not one type of person, it's just a small segment of each type. I think that's a hard thing to market. How do you reach this weird cross section of people? I think audiences are way more open to it than radio programmers and more of the business people. I think they prevent an open audience from hearing a lot of different things that they would be open to.

How do classical musicians react to the band?

People who are specifically cellists of all different ages will make a point to see us. They love it, because they know exactly what we're doing; playing the cello. But I think the classical music world is a pretty tight and closed thing. I've never been involved in it. I don't even know if they know of us, because for us to perform and put out records in a rock world... I don't know that anyone crosses over at all.

I guess they may feel alienated because the music fits in a different category.

I know at one point when I was needing another cellist, I wanted to put up a notice at Julliard. You know, I'm sure they had some kind of job center there. However, the receptionist really poo-pooed it, like "I'm sure no one here would be interested in what you're talking about." Those kind of door closings, you know. I walk away.

What do you think about most of the time?

I think I'm pretty fantasy oriented. I think people that visualize goals, you know, I think that's really good. I make up a lot of fantasies... success stories about myself. I think that then you can make those things true. A lot of soap operas for fun.

Do you write outside of music and lyrics?

I have a few things to say in each show, so that's something that I write every day. That's kind of like joke writing, you know, a very short thing with a beginning, middle, and end. It's kind of abstract. That's very rigorous because I have to do that every day when we're touring.

So you have different stuff to say each night?

Yes. I think I tend to write down a lot of combinations of words and then make something out of that later. Like a lot of the spoken stuff on the record is from abstract lists that then becomes its own thing. It's really hard in making a record to make a spoken thing that somebody can hear more than once. It's hard to make something you can stand to hear more than once, spoken I think...

Well, you did it.

You didn't hear the out takes!

Do you think things in the world are generally getting better or worse?

Well... musically it seems like all kinds of middle-of-the-road publications or voices or whatever are talking about there needs to be something new in music, and I think that's good when that's commonly agreed... because then maybe something new and exciting will happen. I'm probably not that connected with current events and those kinds of things.

Do you watch the news?

I like to when I can, but it goes in cycles. Sometimes I know what's going on, sometimes I don't.

Sometimes I think you can get really caught up in all of it.

Yeah, and also the news is just like rock radio. It's just what they're giving you and it's not necessarily the best or most important information.

Do you think that children should be punished when they are bad?

Yes, I do.

And how do you think they should be punished?

Well, you know spanking is something I can really get behind. The kids in my family were actually given one hard wallop on the butt once in a while. I don't think that's so bad. People make such a big deal out of it. I think it's good to be strict with children when they're small, and be very free with them later when they're able to make their own decisions.

That sounds very reasonable.

That's how my parents were, and we all turn back into our moms and dads.

Do you feel similar to your mom and dad?

Yeah, I think that's kind of inevitable. Most people probably try to avoid it but it comes out in weird ways.

Did you play with toys when you were small?

Yes. I know that I spent whole summers without ever going outside. There were my physical, imaginary games with my sister... that kind of stuff. Forcing her to assume some kind of character. I think we did a lot of Victorian maid kind of stuff actually. That probably came from books.

Did you play with dolls?

Yes, I did Barbie and all that kind of stuff and had an obsession with teenagers. That probably comes from television.

I remember when I was small I thought teenagers were really important.

Like a celebrity or something. I think that comes from t.v.

It probably does.

Now that I'm older than teenagers, I still idolize them. Probably more of a love/hate relationship now probably.

Which do you think is more important: past, present, or future?

You know, I really think that they're so equal because when people say how important and good it is to live in the now, I really believe that,even if I don't do it enough myself. The past is such a huge, exciting thing... all the things that humans have done and made. The future is all those great things come together and we don't even know what it is. They're three wonderful things.

Where would you like to be in the future?

Ummm... some sort of rural, after-the-bomb thing sounds romantic. When there's just a few people left and there's the crumbled shells of some great, old buildings out in the middle of nowhere. Something I think about all the time... you were asking what I think about... is I really like to picture myself with some historical figure that I might be into at the time now. To watch t.v. with Mary, Queen of Scots of something... that kind of thing.

Have you ever done seances?

My friends and I do Ouija board a lot. We would get some fantastic stories, and we had a mystery that we verified with names and phone numbers on Long Island... but it's only really good when this one guy, Jerry, is playing, so I have my suspicions. He either has magic powers, or he's a cheater. I don't know which it is.

Do you believe in telepathy?

Yeah, I think people have some abilities there that we probably don't know about. Intuition can happen. But it might just all be that you're imagining a logical outcome.

From: https://babysue.com/Rasputina.html

7Horse - Meth Lab Zoso Sticker

LA’s 7Horse are a duo. Some call them the Two-Man Rolling Stones. It fits. They have a new album. It’s called Livin’ In a Bitch of a World. Like their previous two albums, it’s filled with fuzzy, blues-y, raw n’ ripping odes to the cheapside of life, story songs about hard luck gamblers, street-fighters and steely-eyed tough guys. Also like all of their previous albums, every word is true, more or less. Take the first single, Two Stroke Machine, for example.

“Yeah, that song is about me and my dad, an incident that happened when I was about 2 years old,” nods 7Horse’s drummer-slash-frontman Phil Leavitt. “My dad was a loose cannon back then, kind of a Charles Bukowski type figure, and there was a beef in the house between him and my grandparents, and he pulled a gun on them. My mom was there too. My dad plays a cameo in the video for the song. He loves it. My parents are long divorced but my mother, she had a visceral negative reaction to the song. She really didn’t like it.”

“And she’s generally a very big fan of this band,” laughs guitarist Joei Calio. “It was an interesting situation to say the least,” says Leavitt. “ I have never played a song for my mother and had her go, “Oh I hate that”. I think because it brought her back to that day.” “When he brought that to me, I thought it was one of the best opening lines I’d ever heard,” adds Calio. “So clean and pure.”

Leavitt’s background looms large in 7Horse’s sound and vision. He grew up in Las Vegas, during its heyday of excess and depravity in the 1970’s. It’s there in the lyrics and the atmosphere and in their live show. I witness them bashing out their smoky barroom rock’n’roll to a sparse but enthusiastic crowd one lonesome Sunday night in Boston and the room was thoroughly transformed into a seedy lounge full of creeps and dames and murder kings through Leavitt’s witty banter and the band’s full-bore dedication to authentically hard-edged rock’n’roll.

“This show we do, it’s like a combination of a rock show mixed with like a Las Vegas lounge act,” explains Leavitt. “I grew up with that classic show business world. You know like when you’d stay up late to watch Johnny Carson and see guy like Don Rickles? That was my actual childhood. I grew up in Vegas in the 70’s, the old school Vegas. People wore suits and I was running around casinos when I was in single digits. I had a job at the casino when I was 13. I grew up in that environment, and it makes it’s way into the lyrics. We’re coming from a dirty rock’n’roll angle, we want to perpetuate that atmosphere.” From: https://www.loudersound.com/features/7horse-a-story-of-gunplay-death-blues-perseverance-and-survival

Molly Tuttle & Golden Highway - She'll Change

Cindy Howes: Molly Tuttle, welcome to Basic Folk again. It’s so great to have you back on the podcast.

Molly Tuttle: Thank you so much for having me back. It’s great to be here with you guys.

CH: So, when approaching the writing on City of Gold, you asked yourself, “How do I tell my story through bluegrass?” Which I can relate to, as somebody who’s sort of tried to distance themselves from folk music for a really long time. And now I am fully leaning into it. So, I take it as you asking that question of yourself, like “How can I fit my Molly Tuttle-ness into a world that can be rigid, patriarchal, and maybe different from what you stand for.” So how true is that? And how have these songs helped you take control of the bluegrass narrative and tradition?

MT: I think that’s something I’ve always kind of struggled with. I remember when I first started writing songs, I just thought, “I don’t know how to write a bluegrass song.” I can write a song, but they never ended up sounding like bluegrass to me and I just didn’t feel like my story fit into the bluegrass narrative of the songs that I grew up singing.

I always loved songwriters like Hazel Dickens, who wrote bluegrass songs from a woman’s perspective, wrote songs about the struggles that she had as a woman in the music industry and as a working woman, and songs about workers’ rights and things she believed in. I grew up with two really strong role models, Laurie Lewis and Kathy Kallick, out in the Bay Area. I remember early on I would go out to Kathy Kallick’s house and she would make me tea and listen to my songs. She always told me that when she was first getting started writing bluegrass songs, she kind of felt the same way as me. Like, maybe her story didn’t belong in the genre. But she met Bill Monroe, and he encouraged her, “Don’t try to write a song that sounds like a song I would have written, write a song from your own perspective.”

So she wrote a song called “Broken Tie” about her parents getting a divorce. She said every time she was at a festival with Bill Monroe, he specifically requested that song. That was an inspiring story to me. But when I started writing songs for Crooked Tree, it was suddenly like a floodgate opened. I think I just found my people to write with, found my groove, and ended up with a collection of songs that kind of told my story, told about things I believed in, and told my family history and personal experiences. And then other songs that were just, you know, from a woman’s perspective, or from a perspective that I resonate with. For City of Gold, it was fun to kind of continue that and also expand it to be songs that I felt like were inspired by my band members, or inspired by experiences we’d had on the road. This felt more like a collective vision in a way.

Lizzie No: Okay, let’s talk about Crooked Tree. The title track from your last record was partly inspired by your experience living with alopecia. You’ve said that as a kid you would wear hats and then wigs, and then you learned to talk about your wig. Eventually, you started to get more comfortable going without. Now that you’re touring with Golden Highway a ton, you sometimes take your wig off when you play that song, which is such a powerful moment of joy, courage, and vulnerability. As a performer, I can relate to those moments where you bring a little bit extra of yourself and you share a part of yourself that you might normally keep private. How do you get to that right mood? How do you gauge if the crowd is like the right crowd to share about your alopecia experience?

MT: It’s also based on how I’m feeling. I took off my wig a few times last year. But I didn’t do it as much as maybe I wanted to, or maybe I should have, just because I wasn’t always sure what to say. I’ve had so many experiences of trying to explain alopecia to people and they still think I’m sick or still feel bad for me. And it’s so hard sometimes to put it in words that aren’t going to bring the mood down at the show, you know, I want people to be having a good time. I want it to be this fun, inspiring moment, not a moment where people can go, “I feel so bad for you.” Recently, I performed and told my whole story for a keynote speech at this alopecia conference out in Denver, Colorado. I think that was such an important step for me. Just getting to share my story and reflect on the pain of growing up having this really visible difference, but also like, the joy and why it’s so important to me to share that with others and share the message that it’s okay to be different. It’s okay to be a “Crooked Tree.” This last weekend, we played in Michigan, and I did take off my wig and I felt like I finally nailed what I said and the perfect mood. Everyone was cheering and it was just a moment of celebration. I think I’m gonna just continue doing that more and more, but I find that it’s so helpful for me to check in with the alopecia community and feel that support from other people who know exactly how I feel. That makes me feel confident to share my message with the world and maybe sometimes be like, “I don’t care how it’s received, maybe I’m not sure how it’s gonna be received, but I’m going to do it anyway.” That just comes with time. And I guess I’ve had to grow kind of a thick skin. It used to be a lot harder for me.

CH: The new album, City of Gold, the songs were mostly written by you and your partner Ketch Secor of Old Crow Medicine Show. What is the writing process like with you and Ketch? Like, how do you bring out the best in each other’s writing?

MT: We’re both quite different writers. He’s very fast paced. He throws out ideas and lines. While I’ll think it over. I’m kind of more internal. I think about the lines. We balance each other out in a way where I might think a lot about what exactly we are saying, and then he’s good. If I get stuck on something, he can kind of keep it moving. But our writing process is always different. It’s nice, because we’re together a lot. So we can write in a lot of different circumstances. Some of the songs we wrote in the car, like on a road trip, just throwing lines back and forth. Maybe he’d be driving, I’d be writing the lines on my phone. Maybe we’re talking about something at home or listening to music and sitting down with instruments, kind of more the conventional way of writing. I find it so hard to fit writing into my life, especially when I’m on tour and I’m on the go so much. It’s so nice that we got into a groove with it, where we were just doing it all the time, and it felt more naturally intertwined into my day-to-day life.

LN: The bluegrass community was a huge source of inspiration for you. Of this record, you said, “One of the things I love most about this music is how so much of the audience plays music as well.” And that you hope that people will sing along and maybe play those songs with their friends, almost like we’re all a part of one great big family. Now, how do you walk the line of making a sophisticated, bitchin’ bluegrass record, while keeping it simple enough for others who might not be musical geniuses to play along?