The debut album by Throwing Muses was released in 1986, at the beginning of my sophomore year of college. Back then I had a friend who listened almost exclusively to artists on the British independent label 4AD, and I wanted to have musical tastes as esoteric as his. He told me that Throwing Muses—who lived in Boston, like we did—was the label’s first American signing, and I bought their record without having heard a note of it, only moments after a clerk in the Harvard Square branch of Newbury Comics slipped it into the “new releases” bin. I reasoned that since the record had come from England, and Boston was the easternmost major port in the United States, I was probably the first person in America to buy it, and for a long time I went around saying this. At that time my friends and I played a lot of I-heard-them-before-you-did—I saw R.E.M. in a tiny club with only fifteen other people before they were famous—and naturally there was a little of this involved, but my proprietary feelings toward Throwing Muses were more personal. I had finally found the music that was meant for me. Back in my dorm room I studied the inner sleeve of the record trying to make sense of the lyrics. Sometimes an obvious meaning broke through. “Home is a rage, feels like a cage”: I understood that. But even when coherence was just out of reach, the music completed the logic of the songs. I heard the anguish and frustration in Kristin Hersh’s thin, quavering voice. The instruments churned and chugged, or mapped out herky-jerky rhythms, and frequently broke into a wild, cathartic hillbilly dance.

He won’t ride in cars anymore

It reminds him of blowjobs

That he’s a queer

And his eyes and his hair

Stuck to the roof over the wheel

Like a pigeon on a tire goes around

And circles over circles.

I had never before heard a song with the words queer and blowjob in it. But I had just come out of the closet, and this song, “Vicky’s Box,” somehow made me feel acknowledged. The wheel and the pigeon were mysterious, but they felt true. It was as though the band had detected the dark, metallic sadness that I was so urgently trying to believe wasn’t there. “Kristin puts a lot of pictures in front of you, and you draw your own conclusions about how they all fit together,” David Narcizo, the drummer for Throwing Muses, tells me during a recent Skype conversation. “You also don’t have to if you don’t want to. I used to liken it to early R.E.M. and Cocteau Twins. I didn’t know what they were saying, but there are moments in those songs when I would think, I totally feel that. You get a sense of something genuine, but you don’t have to define it.”

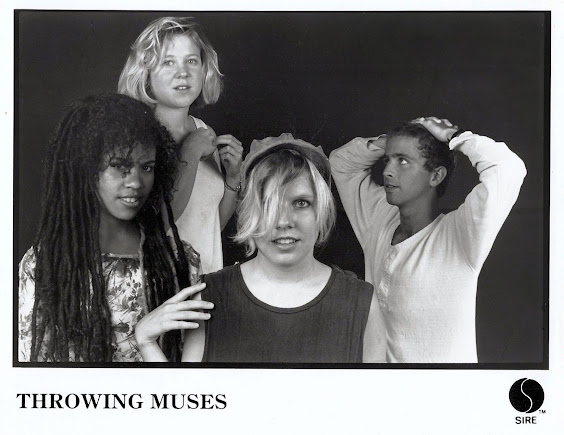

Hersh formed Throwing Muses in the early 1980s with her stepsister, Tanya Donelly, while they were teenagers growing up on Aquidneck Island on the Rhode Island coast. Both played guitar and sang; in the DNA of Hersh’s early songs you can detect traces of such inventive and intuitive punk bands as the Raincoats and X. The sisters recruited Narcizo, a childhood friend, to play drums, and Leslie Langston, a local musician, to play bass. Hersh was the primary songwriter; Donelly contributed one or two songs per album.

An impressionistic timeline:

1987: Throwing Muses play a surprise Saturday afternoon show at the Rat, a grubby basement club, and I watch while standing on a chair at the side of the room. The ceiling is so low that I can touch it. The band performs a few new songs, and this is when I first hear Hersh’s “Cry Baby Cry,” a clarion call against despair that still has the power to remind me of why it’s good to be alive. The room swells with sound, and for a moment I have the exhilarating sense that I’m actually inside the music. “The whole point of doing a show is to turn a room into a church,” Hersh says twenty-six years later when I interview her by telephone, and I remember how that concert gave me a feeling of transcendence that I had never felt inside a real church.

1988: At Newbury Comics (I lived at Newbury Comics), a bossy friend whose every word I hang upon sees me pick up House Tornado, the band’s new, second album, and says, “You’re not going to buy that, are you?” I sheepishly let it fall back. I’ve started frequenting Boston’s dance clubs, and my friends and I are fans of arch and polished British bands like Pet Shop Boys and New Order. It takes me a while to learn that I don’t have to take sides.

1991: I read a glowing review of a new Throwing Muses album, The Real Ramona, and regret that I ever turned my back on them. I buy all the albums that came out while I wasn’t listening.

1992: Donelly begins writing more songs and leaves to form Belly, her own band, which includes two brothers with handsome surfer looks. I so eagerly await the appearance of their first album that on the night before its release I have a dream that one of the brothers asks me to be his date to the launch party. Meanwhile, Throwing Muses regroups as a three-piece, with new bassist Bernard Georges.

1994: Hersh’s first solo album, Hips and Makers, appears. Her songs have by now taken on a yearning sweetness. Nonetheless, when I play the single “Your Ghost,” for my guitar teacher, because I want him to teach me the fingering, he has difficulty figuring out the time signature. “Who’s that singing with her?” he asks me. “Michael Stipe,” I reply. “Oh,” he says, “well, no wonder.”

1996: I pretend I am sick, employing some dramatic fake coughing, so that I can leave work early and buy a Throwing Muses album called Limbo on the day of its release at an HMV in midtown New York that is now a Build-A-Bear Workshop. (And maybe, since it’s barely lunchtime, I am once again the first person in America to buy it.) Not long after, the band leaves behind the world of corporate rock. Living in different parts of the country, they tour and record together less frequently—their next album doesn’t appear until 2003.

2011: Hersh, an early adopter of the pay-what-you-wish model, posts solo demos for a new Throwing Muses project on the CASH Music Web site. I am immediately convinced that they are among the best songs she’s written.

Purgatory/Paradise—the band’s first album in ten years—comes with a downloadable commentary track during which Hersh and Narcizo chat about the music while it plays in the background. There’s a heartbreaking song called “Dripping Trees.” “You a clean spark or a twisted parody? Well, look at me,” Hersh sings. “These wicked memories—it all comes down, eventually.” The melody sounds like something tumbling earthward, in slow, sad, stately spirals, and yet still landing perfectly on its feet. “This is such an ‘us’ song,” she says on the commentary, and laughs. “It’s so us because you can’t tell if it’s saying something good or something bad … Anthemic and pathetic at the same time.”

From: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2013/12/17/jewel-toned-insides-talking-with-throwing-muses-and-tanya-donelly/

DIVERSE AND ECLECTIC FUN FOR YOUR EARS - 60s to 90s rock, prog, psychedelia, folk music, folk rock, world music, experimental, doom metal, strange and creative music videos, deep cuts and more!

Monday, July 22, 2024

Throwing Muses - Sunray Venus

-

My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless is the rare album that made its way into my collection without me hearing any of it until minutes after layin...

-

Today’s classic Motown song of the day is “Bernadette” by the Four Tops. It was released in February of 1967 and peaked at #4 on the Billboa...

-

OOIOO - Gold and Green - Part 1 OOIOO - Gold and Green - Part 2 01. Moss Trumpeter 02. Tekuteku Tune 03. Grow Sound Tree 04. Mountain ...

-

From the jaunty tilt of her scarlet beret to her languid drawl, Rickie Lee Jones was the epitome of effortless cool in 1979. That winter, po...

-

A decade before Fleetwood Mac’s critically wounded marital relationships spilled blood on the tracks of the classic Rumours album, The Mamas...