At the tail end of 1987, the kings of indie-pop released their fourth and final studio album Strangeways, Here We Come a little over a year after their masterpiece The Queen is Dead. We at Melophobe certainly did not hold back with our praises with that record being one of the five albums to receive a perfect 10/10 score from us. Between the two final studio albums, two unique compilation albums were also released showcasing a handful of unreleased tracks rather akin to the style of The Queen is Dead with Panic and Ask at the forefront. In the Smiths final go at it, they seemingly tried to separate themselves from the jangle-pop sound which at this point, went hand in hand with the perception of The Smiths sound as a whole. To their credit, this album definitely exhibits a stylistic evolution, and has a sound more so in the alternative rock family (although it’s still an oceans width away from the alternative rock sound of R.E.M or The Pixies) than the indie pop family, at least in the context of the Smiths sound. All in all though, Strangeways, Here We Come was a great and largely under-appreciated record at a time when the alternative rock world was very malleable.

The room filling keyboards and microphone effects which kick off the album on A Rush and Push and the Land Is Ours set the stage for a stylistically different sound than the previous studio album; in fact, there are no guitars at all in this song. The Smiths with no guitars!? And the best part is, they nailed it. Although Johnny Marr is not wielding his 6 string on this song, Andy Rourke still lays down a great bassline raising the question, why do all The Smiths basslines go so hard? Following the guitar free opening track, fear not, Marr bluntly comes back in with a more classic sounding guitar forward song with I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish.

The star child track from the final studio album (at least to the masses) was the lead off single Girlfriend In a Coma. Short, sweet, and very concise, this song just shows what the Smiths do well - jangly, indie pop. No matter how hard they may have tried to separate themselves from that tag, they are just so iconic and good with that sound. The lead-off single finds itself with nostalgic, almost medieval sounding English folk melodies played so gracefully by Johnny Marr on his acoustic guitar. Although it may not be well noticed, and it certainly has not been talked about much, the bright indie folk sounds of this song were decades ahead of its time with the indie folk scene not popping off until the early 2000’s. For me though, it's the musically interesting third track on the album Death of a Disco Dancer that steals the show with its massive outro and interesting guitar work almost akin to what you might expect from a band like Radiohead. The Smiths had never released a song quite like Death of a Disco Dancer and although they made the sound their own in their unique Smiths fashion, that was a seemingly experimental and out of left field fantastic track.

The impact The Smiths had on indie and alternative music really cannot be overstated. They made it sexy, they made it accessible but most importantly, they were really good musicians. No one is saying Strangeways is The Queen is Dead, but it is great in its own right and allowed The Smiths to branch out a tad more before they vanished into the sunset. The legacy of The Smiths lives on today in the indie world, and is not going anywhere anytime soon. Just as most of what The Smiths have released, the songs hold up today as strong as ever. From: https://www.melophobemusic.com/post/the-smiths-strangeaways-here-we-come-retrospective-review

DIVERSE AND ECLECTIC FUN FOR YOUR EARS - 60s to 90s rock, prog, psychedelia, folk music, folk rock, world music, experimental, doom metal, strange and creative music videos, deep cuts and more!

Thursday, July 11, 2024

The Smiths - Girlfriend In A Coma

Solstice - Bulbul Tarang - Live at Grand Chapel Studios

Thankfully, I chose to listen to (for the first time) Light Up in the morning. I wrote the review from that wonderful listening perspective. I did it because this wonderful album sounds like a bright, morning wake-up call. A soft, simple awakening to a summer or spring day (even though it’s winter, as I write this review). Light Up will be released January 13th, 2023 and it follows in the footsteps of Solstice’s very successful release, Sia, from 2020. Solstice is not a new band. They have been around since founder Andy Glass, who plays lead guitar, assembled the band in 1980 with violinist Marc Elton. But the band has a new sound and a relatively new voice, that of Jess Holland on lead vocals (she joined in 2020). Jess recently was voted amongst the top Female Vocalist of 2022 from Prog Magazine’s Reader’s Poll. Jenny Newman plays a mean fiddle and violin, Peter Hemsley plays explosive drums, Steven McDaniel plays amazing keyboards and Robin Phillips plays bass.

Light Up is a wonderful album to review as a first album of 2023. It will be a great year if more of the releases that I expect this year will fulfill expectations as well as Solstice have with Light Up. This band begins with one of the best voices from across the Atlantic. Jess sings in the title track,“Light Up”: “Let the morning in and the day begin. Wash the night away. There’s a place in here. She will keep you near. Don’t look the other way. Let the new light in. And begin again. Find another way. Here’s a place to start. Listen to your heart. See a brighter day. Give your heart away”. What a wonderful way to start a new year, eh? I think so. Love this song - already one of my favourites for the early new year.

Solstice was also voted one of the top progressive bands of 2022 by that same Prog Magazine Reader’s Poll. And it is no wonder. They are a dynamic band of musicians which provide a jazzier, Canterbury style of prog which is simply amazing. Andy Glass looks and at times sounds like one of my favourite guitarists, Steve Howe of Yes, and Jenny Newman on fiddle and violin make this band one to be reckoned with for the future of progressive rock music. And, even though this is an EP, the tracks are long enough and full of enough beautiful music to make this compilation fit well within the composition of most of the classic and modern progressive albums that you may already know, own and love.

“Wongle No. 9”, is no “Bungle in the Jungle”. Instead, it’s what might happen if Yes was to play alongside Steely Dan live. Truly inspirational in every way. Absolutely powerful jazz prog. You can dance to it. When was the last time you could say that about prog? I can definitely hear in this music how this band was so successful on the festival circuit this past summer with songs like this one. Andy’s cutting electric guitar soloing, Jenny Newman’s ripping violin solo, Jess Holland’s clear vocals, Peter Hemsley’s perfect drum beat, and Steven McDaniel’s radiant keyboards keep this musical train running at top speed. Speaking of Yes, Robin Phillips brings back memories of Chris Squire on bass. Such a great follow up to the title track and EP opener.

Then they hit you with Jenny Newman coming at you full speed with fiddle, the likes of which you probably haven’t heard since Charlie Daniels’ “Devil Went Down to Georgia” which lit up the amps and speakers back in the 1970s. “Mount Ephraim” also has some fantastic bass fun from Robin Phillips who keeps good pace with Newman and Hemsley’s solid drum beat. McDaniel’s adds some soft keys along with Glass’ guitar soloing. Jess sings around midway through this instrumental extravaganza. She takes the song higher and adds words to this wonderful fiddle symphony. A beautiful symphony of sound that just takes you over.

“Run” is absolutely not what you were expecting from that title. After all this cool, relaxing music, I don’t think anyone wants to run. But that is not what Jess and the band are talking about here. In fact, it is a confident, calm statement that, if you call, Jess will come running home. A beautiful keyboard and solo guitar statement, with Newman’s violin and soft drumming. Beautiful, and so wonderfully calming. Keep this one near, with a glass of wine and soft light, at the end of the evening. After all the work, or the things that you do during the day, sit back, relax and enjoy this song. “Home” is another wonderful instrumental journey for the band with Jess’ soft vocals adding to the sound. Home is where everyone’s heart is, and the band knows it to be true. This song encompasses everything we all appreciate about where we love to live, wherever that is. We all wish we were going home. Another wonderful Glass and Newman soloing experience. Just sit back and let them dazzle you again!

“Bulbul Tarang” is a string instrument from Punjab, which evolved from the Japanese taishōgoto, which likely arrived in South Asia in the 1930s. Andy Glass uses it to full extent on this exquisite piece of music to close the album. The harp-like sounds at the opening immediately remind you of some of the wonderful music off one of your favourite Yes albums. But this innovation is Glass’ and Solstice at their best. However, the comparisons are fair. This song sounds like something that Jon Anderson, Steve Howe and Chris Squire may have thought of and that is meant only as a compliment. However, Newman’s violin adds an Eddie Jobson-like feel to the atmospheric sound. Jess, at times, sounds like Jon Anderson on, say, “Onward”, or something off Tormato, Jon’s solo albums, or the ones with Vangelis. What a beautiful way to close this album. Steven McDaniel, finally gets front stage, with a beautiful, soft, piano solo. I wish it was longer, but as Pete Townshend sings, sometimes “a little is enough”.

Light Up is already one of my early year, favorite prog albums. There is a lot more to come this year, but Solstice has grabbed my ears early. This should definitely make my top 10 Prog albums of the year. Everything you could want and imagine out of a progressive rock album. Blistering, Hackett/Howe-like guitar solos, keyboards that melt your heart, great bass and drums, and a wonderful voice, as well as something more. Something that you didn’t expect. Violin to make you want to come back for more. Not Kansas-like violin. A unique and music enhancing violin sound. From: https://www.solsticeprog.uk/reviews/light-up

Wednesday, July 10, 2024

The Flying Burrito Brothers - Christine's Tune

The Flying Burrito Brothers were a country rock band which formed in 1968 in Los Angeles, California. The band’s original lineup consisted of Chris Hillman (vocals, guitar), Gram Parsons (vocals, guitar), Chris Ethridge (piano, bass) and Sneaky Pete Kleinow (pedal steel guitar). Later members of from the band’s initial existence included Eddie Hoh (drums), Jon Corneal (drums), Bernie Leadon (guitar, vocals), Michael Clarke (drums) and Rick Roberts (vocals, guitar). The group originally disbanded in 1972 following Hillman’s departure. Kleinow and Ethridge instigated a reformation of the band in 1975 which continued through 1984. The band was reformed once again in 1985 and were disbanded for a final time in 2001.

The band best known as the “Flying Burrito Brothers” actually ‘borrowed’ their name from the original “Flying Burrito Brothers”, composed of bassist Ian Dunlop and drummer Mickey Gauvin, bandmates of Parsons from the Boston-based International Submarine Band, plus any of a loose coalition of musicians, including Parsons himself from time to time. In a deliberate choice of focusing on just creating and playing music without the distractions of the music industry, in 1968 the original Brothers moved from Los Angeles to New York City. From this base they continued to tour the Northeast playing their eclectic traditional/rockabilly/blues/R&B-oriented version of rock, using the name “The Flying Burrito Brothers East” after Parsons’ group became famous.

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, Parsons and guitarist/mandolinist/bassist/vocalist Chris Hillman thought this same moniker would be perfectly suited to the band they had been dreaming of since early 1968, when, as members of Roger McGuinn’s band The Byrds, they created one of the first country-oriented rock albums, Sweetheart of the Rodeo. They immersed themselves in their vision in their house in the San Fernando Valley, dubbed “Burrito Manor”, even replacing their wardrobe with a set of custom country-Western suits from tailor to the C&W stars, Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors (Parsons’s had marijuana leaf embroidery) and began a period of intensely fruitful creativity. At this juncture, the band also included pianist/bassist Chris Ethridge and pedal steel guitarist “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow.

Their first album The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969) did not sell terribly well, being a radical departure from anything most of the record-buying public (either rock or country) had ever seen, but the group had a cult following which included several famous musicians, such as Bob Dylan and The Rolling Stones. Parsons soon became friends with Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones and left the group after 1970’s Burrito Deluxe, which also saw the departure of Ethridge and addition of guitarist/dobro player/vocalist Bernie Leadon and drummer Michael Clarke (of The Byrds). Rick Roberts replaced Parsons and released a self-titled album with the group in 1971. Kleinow then left to become a session musician and Leadon joined The Eagles. Al Perkins and Roger Bush replaced them, and Kenny Wertz and Byron Berline joined as well, releasing The Last of the Red Hot Burritos (1972), a live album. The band fell apart. Hillman and Perkins joined Manassas, while Berline, Bush and Wertz formed Country Gazette. Roberts reassembled a new group for a 1973 European tour, and then began a solo career before forming Firefall with Michael Clarke.

As Gram Parsons’s influence and fame grew, so did interest in the Flying Burrito Brothers, leading to the release of Honky Tonks (1974), a double album, and the recreation of the band by Kleinow and Ethridge in 1975. Floyd “Gib” Gilbeau, Joel Scott Hill and Gene Parsons (no relation to Gram) also joined, and the band released Flying Again that year. Ethridge was then replaced by Skip Battin for Airborne (1976), followed by an album of unreleased early material, Sleepless Nights. For the next few decades, the group released albums and toured and had a country hit with “White Line Fever” (1980, a cover by Merle Haggard) and then became the Burrito Brothers. Headed by prolific songwriter and ace guitarist John Beland and Gib Guilbeau, and normally featuring Sneaky Pete, this incarnation scored moderately well on the Country charts in the early 1980s. Through numerous incarnations (including Brian Cadd for a time), the band released albums and toured throughout the 1980s up till 2001 when John Beland “officially” ended FBB. While the bands work during the 1980-1999 period was exceptional, after 1984 none of the many releases had any chart impact. Sneaky created a Burritos spinoff in his new band Burrito Deluxe, which featured Carlton Moody on lead vocals and Garth Hudson from The Band on keyboards. While a good band, there has never been any real continuity with the true Burritos and this group can not be considered anything more than a spinoff. Pete however, left the band due to illness in 2005, leaving no direct lineage to the original masters. From: https://thevogue.com/artists/the-flying-burrito-brothers/

L'Rain - Two Face

On her piercing self-titled 2017 debut as L’Rain, Brooklyn artist Taja Cheek sifted through the aftermath of her mother’s death with roaming sensitivity. Intimate field recordings, tape loops, and fragmented harmonies resembled loose sketches, yet L’Rain’s scattered structure framed an astounding, up-close document of grief. Fatigue, Cheek’s second album, once again looks inward, but this time allows more light into the corners. It’s a graceful record whose wearied landscapes of synth, air horn, strings, and saxophone distill a suite of low moods—depression, regret, and fear—into resilience and hope.

“What have you done to change?” demands Buffalo alt-rock artist Quinton Brock on Fatigue’s blaring opener, “Fly, Die,” a question that weighed heavily as Cheek put this music together. The album’s nonlinear framework replicates the elliptical way the mind works through intense emotions, twisting in different formations until it fractures into a breakthrough. Some of these diffuse songs evolved out of voice memos Cheek made for herself or in collaboration with others, but while her music can be intentionally illegible, it’s never unapproachable. Fatigue’s swirling blend of orchestral groans and human whispers evoke a state of subconscious drift where self-growth is nurtured in real time. It’s a way of taking stock of the bruises of life.

Cheek and co-producer Andrew Lappin’s work is painterly and methodical, daubing vocal loops over clattering percussion, sweeping strings, and resonant synths to create a shapeshifting strain of experimental pop. On the shattering standout “Blame Me,” she sings in a nimble voice over fingerpicked guitar: “You were wasting away, my god/I’m making my way down south.” Jon Bap and Anna Wise’s background vocals form an armature of strength as Cheek’s words grow more woeful: “Fought my demons until you were old—maybe ’cause you love me/Thinking ’bout it lately: future poison-blooded little babies.” Wherever Cheek goes on Fatigue, the ghosts of regret and trauma follow closely behind, an emotional state that colors the album in foreboding shades even as she creates space to recover and improve.

Like L’Rain, Fatigue is marbled with personal recordings: Dishes being washed in the sink beneath a piano melody on “Need Be,” a voicemail from her mother buried in “Blame Me.” The clips imbue the music with fleeting traces of closeness and familiarity. Cheek approaches them from a distance, recontextualizing some of the most heartfelt or difficult moments of her life in song. The mercurial, six-minute highlight “Find It” begins downcast, with a metronomic synth loop and the repeated mantra, “Make a way out of no way.” Screams echo through the sluggish beat as coming through a wall; the dust settles on an organist and singer performing the gospel song “I Won’t Complain,” recorded at the funeral of a family friend. Cheek intones over it until the song crests in a rapturous, overwhelming finale, with no less than 13 musicians contributing to the commotion. It’s easily the most poignant song she has ever made, a deeply felt, Biblically minded portrait of forging a path out of darkness. Yet the journey has room for lightness and humor, too, like the “oops” that slips into the end of “Walk Through” or the wacky vocal affect of a former roommate on “Love Her.” On the brief “Black Clap” and the rhythmic, low-lit “Suck Teeth,” Cheek incorporates the percussive sounds of a handclap game she made up with multi-instrumentalist Ben Chapoteau-Katz, a way to pay tribute to the joyful sound of childhood hand games played by Black girls.

Cheek upends expectations in more direct pop and dance traditions, too. On “Two Face,” a roving piano line and stuttering samples melt into a soulful, psychedelic throb as she ruminates on a failed friendship. “I can’t build no new nothing no new life no new nothing for me,” she trills in a singsong cadence, the words bouncing over oscillated coos. The lyrics on the tense “Kill Self” are even more unforgiving: “Did you see me chew myself out?” she asks, voice rippling in a cascade over shuffling percussion. “Hear the gnawing?” At once the album’s darkest and most propulsive moment, “Kill Self” eventually assumes a seething dancefloor pulse, bending skillfully toward structure without abandoning Cheek’s wandering impulses.

Fatigue ends with the beatific “Take Two,” a spare reconfiguration of “Bat” from L’Rain. She repurposes the song in a similar way to her field recordings, as raw material to mold into an unfamiliar shape. Stripped bare of percussion and transformed into an airy, droning spiritual, Cheek’s voice unfurls in billowy, Auto-Tuned tones as she repeats the words, “I am not prepared for what is going to happen to me.” In her skyward voice, the sentiment is more life-affirming than terrifying, suggestive of infinite possibilities. There is no fixed road toward healing, Fatigue reassures us; there is only the way forward. From: https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/lrain-fatigue/

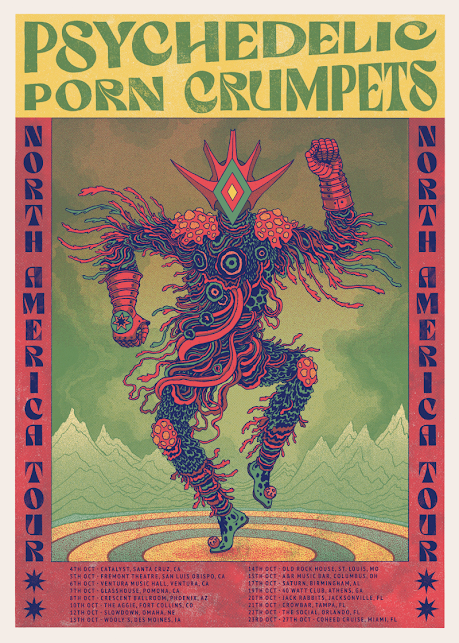

Psychedelic Porn Crumpets - Mr. Prism

Perhaps more than in any other country – although there is fierce competition – Australia’s music culture is linked to the outdoors and festivals. A place of vast expanses and desirable weather will do that. Considering the enormity of the country too, a national tour can feel like a world tour, certainly in the sense of exhaustive travelling. Bands from the country – Spacey Jane, Ocean Alley, Skeggs, or DMA’s for example – thrive in the live setting, their years defined by festival slots and incessant gigs. Australian music is also indelibly linked to psychedelic rock, from psych revival bands in inner Melbourne to the idyllic revivalists from the coastal towns. Tame Impala and King Gizzard may have taken it to the world, but Australia’s psych-rock tradition thrives supremely on its own. Psychedelic Porn Crumpets adhere to both of these things: they are ferocious performers and festival favourites, and they also bang out psych-rock hits at an alarming rate. It’s fortunate, then, that their country’s superior handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has meant that the Crumpets’ hazy tunes can be enjoyed outside as touring slowly but surely returns to Australia, for their songs are designed to be heard from within a messy moshpit or under the sun.

New album SHYGA! The Sunlight Mound opens with “Big Dijon”, a soothing swirl of contemplative rhythm, its lyrics inane psychedelic nonsense about a curious aardvark. Once that’s out of the way, the unceasing energy begins. The Perth band can appear ridiculous to an outsider – just consider their band name – but behind the whimsy and the folly is genuine technical ability. Harbouring their love of The Beatles and Black Sabbath, they spin it into relentless turbo-charged guitar riffs and earnest melodies. That love of the Fab Four shines during the shimmer melody of “Mango Terrarium” or the Sgt. Pepper’s-lite “Glitter Bug” and “More Glitter”. Before those, “Hats Off To The Green Bins” is a delightful ode to hastily cleaning a decrepit share house before a landlord arrives to inspect. The first half of SHYGA! contains most of the sharper hits, while the guitars on the second half are allowed to roam looser and longer. Apart from a few tracks like the interlude “Round The Corner”, the guitar riffs dominate. They thrash and fizz and never let up; it can have a bit of an enervating effect after so much – death by guitar.

It’s the lyrics that betray a band at a crossroad. “Tally-Ho” is a quintessential Crumpets track, featuring a wonderful metaphor for cocaine (“One more line of avalanche-winterland-handicap / Bleeding from the nostril”). Such a song is why they are, above all, a band for the fans. A review of their music can only go so far, for Psychedelic Porn Crumpets exist for the people like them: the festival-goers, the people that they used to be; as they now occupy the stage, they want to give back to their fans some anthems that they can relate to. This is who they’ve always been. It’s emphasised by main songwriter Jack McEwan’s description of one of SHYGA!‘s tracks, “The Terrors” (a term for the anxiety and despondency of the days following a big weekend of partying): “I wanted to write a track that paid homage to where Porn Crumpets began, back in our drug-ridden cave of a share house at Hector Street. There was a solid group of us on Centrelink, either studying or pretending to work, waiting for our pay-check to arrive so we could pickle the membrane and substitute reality for a while, very much in the name of science. The classic Australian coming of age saga.”

The crossroad arrives when they show signs that they’re considering their lifestyle. The raw punk energy of “Sawtooth Monkfish” belies thoughtful reflection on the effects of their hedonism; after listing all the different types of alcohol that they’ve consumed on “Tripolasaur”, McEwan sighs “I guess I’ll never know the reason why I feel so vacant.” “Mr. Prism” is about McEwan being informed by a doctor that he should probably quit smoking (“No more lungs, doctor says I’m done”); it’ll inevitably be bellowed back at them by teenagers smoking rollies as at a Mac DeMarco when “Ode to Viceroy” comes on. On the disgustingly-named “Pukebox”, McEwan says “One more day alive / I must be the luckiest boy around / Drinking moonshine my old man made,” before pondering if he’s truly lucky. “Mundungus” is the greatest reckoning with it on the album; “They said at my intervention / You should give drinking a rest,” McEwan begins, and after listing three days of truly awful effects of withdrawal he screams “I ain’t being sober no more.”

The Crumpets end the album with “The Tally of Gurney Gridman”, an illusion after all the noise from before. Beginning like a skidding and heaving rock song that recalls Sabbath or Led Zeppelin, it dissolves into a twinkling and meandering psychedelic closer. The song also sees a juxtaposition in its lyrics; “Life is dull without meaning / But drinking all day makes the future warm,” McEwan sings at the start, and as the contemplative tone arrives he ponders life and its meaning: “There’s no finish line, ticket sign or button to start it all again / Every old man tells me the same / Live while you’re young / Enjoy each day.”

This is Psychedelic Porn Crumpets of today: standing on the edge of two existences. Much of their music, their style, has often valorised excess and hedonism. Here, four albums in, McEwan and his fellow Crumpets acknowledge the less glamorous after-effects that are a considerably larger part of their lives now. Yet, for all of this, they still sound like a band content to party on. Ending the album with the lines “Live while you’re young / Enjoy each day” feels like a message of defiance as much as a moment of introspection. From: https://beatsperminute.com/album-review-psychedelic-porn-crumpets-shyga-the-sunlight-mound/

Dengue Fever - Sni Bong

Dengue Fever’s psychedelic take on the Cambodian pop sounds of the ’60s makes them one of rock ’n’ roll’s most unique success stories. They draw enthusiastic crowds from L.A. to the UK, from Maui to Moscow, and leave critics rummaging through their thesauruses looking for new superlatives to describe their sound. Their appearance at WOMEX, the world’s largest international music conference, cemented their position as a global phenomenon. Amazon.com named their album Escape From Dragon House the No. 1 international release for 2005. Venus On Earth (2008, M80 Records) is the third chapter in the band’s continuing journey to create a unique fusion of Cambodian and American pop.

Brothers Ethan (keyboards) and Zac (guitar) Holtzman started Dengue Fever in 2001 when they discovered they shared a love for the Cambodian pop music of the ’60s. After adding sax man David Ralicke (Beck/Brazzaville), drummer Paul Smith, and bassist Senon Williams, they went looking for a Cambodian singer. Enter Chhom Nimol, who performed regularly for the King and Queen of Cambodia. Her powerful singing, marked by a luminous vibrato that adds exotic ornamentations to her vocal lines, and hypnotic stage moves based on traditional dances, complemented the band’s driving Cambodian/American sound.

The Cambodian pop music of the 1960s seems an unlikely template for an American band, but that sound captivated Ethan Holtzman during a trip to Cambodia in 1997. Before he flew back to L.A., he picked up every cassette of Cambodian pop from the ’60s he could find. Back home, Zac Holtzman had just returned to L.A. after living in San Francisco for 10 years. He’d been listening to a compilation of Cambodian pop and when the brothers reconnected, they decided to play their version of Cambodian rock. They hung out in the Long Beach Cambodian community to find a singer.

“We saw Chhom Nimol at The Dragon House,” Zac Holtzman recalls. “She was already a star in Cambodia and made a living singing traditional music at Cambodian weddings and funerals.” Chhom wasn’t sure she wanted to sing with Americans, but Dengue’s dedication to the sounds of Cambodia won her over. Dengue Fever was an immediate hit, both in the Cambodian clubs of Long Beach and regular L.A. rock venues. They won LA Weekly’s Best New Artist Award in 2002, and actor/director Matt Dillon asked them to supply a Cambodian version of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” for his Cambodian-based thriller City of Ghosts.

The band’s eponymous debut was mostly covers of Cambodian classics, a tribute to the singers and songwriters who were killed by the Khmer Rouge. Their second album, Escape From Dragon House, written almost entirely by the band, was more psychedelic, freer, looser, and more experimental than the debut. The album featured “Ethanopium,” a cover of a tune by Ethiopian singer Malatu Astatke that was used by Jim Jarmusch in his film Broken Flowers. “One Thousand Tears of a Tarantula” was later featured on the soundtrack as well as on the Showtime series Weeds.

In 2005, the band toured Cambodia. It was the first time any band, much less an American one, performed Khmer rock in Cambodia since Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge took over the country in 1975. The country gave Chhom a lot of respect for “Cambodianizing” the Americans. The band met and played with Cambodian master musicians that survived the Khmer Rouge years and recorded those sessions. They hope to use that music on future albums. A documentary feature film of this trip, Sleepwalking Through the Mekong, has received an enthusiastic reception at international film festivals, as well as the Tucson Film Festival, the Silverlake Film Festival in L.A., and the Hawaii International Film Festival, and it had its New York premiere on opening night at the Margaret Mead Film Festival in New York. From: https://www.laphil.com/musicdb/artists/1444/dengue-fever

The Everly Brothers - Cathy's Clown

The Everly Brothers were one of the most important acts in all of American music. There is a reason they were first ballot inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and are in the Country Music Hall of Fame as well. Though some consider their music mostly within the rock realm, the home base for their career was Nashville, and country songwriting duo (and fellow Country Hall of Famers) Felice and Boudleaux Bryant wrote most of their big hits like “Bye Bye Love,” “Wake Up Little Susie,” and “All I Have To Do Is Dream.” But all great things must come to an end, and that’s what happened 50 years ago today, July 14th, 1973 in a rather spectacularly catastrophic fashion. It was the culmination of years of turmoil and conflict between brothers Don and Phil Everly, as well as conflict with the country music industry.

Unlike many of their contemporaries, the career of The Everly Brothers seemed to hit a brick wall in the early 1960s, and they never really rekindled their popular magic later in life. The country music industry was to blame, and it led to a deeper conflict between the two siblings. The well-known guitar player, producer, and country music executive Chet Atkins was a close friend of the Everly family dating back to before the brothers were a duo and were known more as a family band with their father Ike. Chet brokered the brothers’ first record deal with Columbia in early 1956, and also introduced the brothers to Wesley Rose, son of Fred Rose, who was the well-known songwriter and founder of Music Row publishing house Acuff-Rose. Wesley Rose also became The Everly Brothers manager.

In 1961, the brothers had a falling out with Wesley Rose. At the behest of Rose, they only used Acuff-Rose writers, including Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. But as time went on, The Everly Brothers wanted to record other songs. Wesley Rose adamantly refused, so the brothers dropped Rose as their manager. At the time, Acuff-Rose had a virtual monopoly on all the best songs and songwriters in the music business for the type of music The Everly Brothers played. The duo’s falling out with Wesley Rose meant they no longer had access to ‘A’ list song material. Both Don and Phil Everly were songwriters as well, and wrote many of their own songs. However, in a strange twist of fate only fit for Music Row, because the brothers were still signed to Acuff-Rose as songwriters, the falling out with Wesley Rose meant that the brothers lost access to their own material as well, and any material they may write in the future. So The Everly Brothers began recording cover songs, and started writing under a collective pseudonym of “Jimmy Howard.” However, when Acuff-Rose sniffed out what was happening, the publishing house brought legal action against the brothers and obtained the rights to those songs as well. Between 1961 and 1964, one of American music’s most brilliant and popular bands was resigned to singing cover material, and their popularity plummeted.

In 1964, the conflict finally abated with Acuff-Rose, and The Everly Brothers began to record their own material again, along with resuming work with Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. But not only had popular music in America mostly passed them by, due in part to the turmoil, both brothers were now addicted to amphetamines. Don Everly was also taking Ritalin, and eventually suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized due to his addiction issues. By the late 1960s and the release of their album Roots, The Everly Brothers were beginning to turn things around, and remained popular in England and Canada. They were also announced as replacement hosts for The Johnny Cash Show for a stint. But behind the scenes, things were beginning to fray between the brothers. Don released a solo album in 1970, but it was mostly unsuccessful. So they began recording together again for RCA, but the entire time, Don was ready to break away from his brother to be a solo artist.

All of this led up to what was announced as the final performances before a two-year break for The Everly Brothers set to take place at Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, California on July 13th and 14th, 1973. It was supposed to be a joyous occasion for the brothers who knew some space would do them good, and wanted to keep things amicable. But that’s not exactly what happened. The July 13th performances went fine, but by the time Don Everly was set to take the stage on July 14th, he was clearly drunk. He was slurring words and forgetting some of the lyrics to the songs—something unheard of for Don Everly even in his worst state. Warren Zevon happened to be playing keyboards for them at the time, and recalls of the evening, “I’d seen Don perform with the flu and a temperature of 103. I’d never heard him hit a sour note or be anything short of professional in front of an audience. But, this night, he walked onstage dead drunk. He was stumbling and off key and I remember Phil trying to restart songs several times. It was embarrassing.” As the crowd started jeering, Don Everly lashed out at the them, and at Phil. Embarrassed and frustrated, Phil slammed his guitar down on the stage, smashing it. As he walked off the stage, he said to the promoter, “I’m really sorry, Bill, I have to go. I can’t go back on stage with that man again.” Surprisingly, Don tried to continue the show, telling the crowd famously, “The Everly Brothers died 10 years ago.”

Don Everly later recalled to Rolling Stone, “I was half in the bag that evening—the only time I’ve ever been drunk onstage in my life. I knew it was the last night, and on the way out I drank some tequila, drank some champagne—started celebrating the demise. It was really a funeral. People thought that night was just some brouhaha between Phil and me. They didn’t realize we had been working our buns off for years. We had never been anywhere without working; had never known any freedom. We were strapped together like a team of horses. It’s funny, the press hadn’t paid any attention to us in ten years, but they jumped on that. It was one of the saddest days of my life.”

Though the hiatus was supposed to only last a couple of years, it would take another 10 for the brothers to reunite on stage at at the Royal Albert Hall in London on September 23, 1983 in a concert that was recorded for an album and a cable special. Meanwhile, their infamous breakup on stage would go on to define the spectacular destruction of a band in public. The Everly Brothers would continue on and off for the rest of their lives. Phil Everly died in 2014, and Don Everly passed away in 2021. Despite the turmoil the brother duo experienced, they left a legacy that crossed genres and generations, and is still lasting today. There’s nothing like the blood harmonies of The Everly Brothers, no matter the bad blood that came between the brothers at times during their legendary career. From: https://www.savingcountrymusic.com/50-years-ago-everly-brothers-tumultuously-break-up-on-stage/

Martin & Eliza Carthy - Blackwell Merry Night

It’s always a treat to see either of these two, although this is the first time I’ve seen the pair of them perform together (aside from with The Imagined Village). Martin and Norma Waterson, yes; Martin and Dave Swarbrick, yes; Eliza and her band, yes; just dad and daughter, not previously. And the dynamic was a lot of fun, two dry wits together expressing their love for the slightly absurd nature of the music they play, whilst also conveying the genuine emotion that they find in the folk songs — and more recent compositions — that they perform. Not to mention the fact that they are incredibly accomplished musicians, one of whom played the version of ‘Scarborough Fair’ that provided the inspiration for Dylan’s ‘Girl from the North Country’ and Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme’. And he’s still one of the humblest and most genuine people you’ll ever encounter.

The set-list was largely made up of tracks recorded on their joint album, The Moral of the Elephant (2014), though Martin also played a recent acquisition — the name escapes me, and it doesn’t seem to have made it onto the setlist.fm page — that had apparently dogged him for some time before he’d managed to pin down the melody that he was so full of praise for. The fact that, at 76, he’s still collecting and adapting material made this song the perfect example of his mantra that folk music is not about heritage but about life, a mantra reinforced by Eliza’s solo take on ‘Nelly Was a Lady’. The latter is a song written by Stephen Foster and taught to her by a colourful Canadian family friend, described as a great source of ‘hideographs’ (if I remember correctly). The tale of young Foster and his tragic, accidental death is as poignant and vaguely absurd as any you’d find in a broadside ballad (he tripped in his tiny New York apartment and hit his head on the sink as he fell, as there was no space to fall anywhere else); though like many ballads it needs to be read within its historical context. Eliza is a great defender of pop music and the songwriters who are able to write reams of hit songs, whether for broadside ballads, Motown or any other genre. She places the music that she and Martin perform within an ongoing tradition, the two of them noting common reference points and the underlying universality of emotions in these songs: people still love a good lock-in at the pub (Blackwell Merry Night), mothers still suffer the agony of losing their sons to war (Monkey Hair) and six individuals will still struggle to reach a common solution if they don’t work together (The Elephant).

Most of these songs aren’t the anonymous, centuries old pieces of tradition that I suppose many people associate folk music with. The three just mentioned also have named composers, and even the tracks they played with a more mysterious transmission history have been moulded and edited by different singers, performers and composers. An individual who has left their mark on a song is as worthy of discussing as the song itself at this kind of gig. When there’s not a composer or someone to credit the ‘trad. arr’ to, Eliza memorably described the great old ballads as icebergs or glaciers: something that starts off vast, but shears off pieces here and there as it travels the world. It’s perhaps a theory that skims bit close to Russian formalism for my taste, but I can’t deny that folk music does tend to gravitate towards particular types of story. Two grand narratives they put together in their own way were the ‘girl has to be quiet with her lover because her mum’s upstairs and has a vast collection of weaponry for dealing with just such lads’ (I paraphrase, but Eliza described it along these lines!) and ‘died of love’. Examples of the former that may be familiar are Silver Dagger and Kate Rusby’s ‘The Cobbler’s Daughter’, whilst the latter tends to crop up all over the place, often tacked onto the end of a narrative that’s about one sort of ill-fated relationship or another (many of Jim Moray’s preferred traditional songs seem to end like this…). The idea of the mother wanting to save her daughter from an unhappy future relationship, and the intensity of heartache (whether it’s after a break-up or a death) are at the core of these songs, and it’s not hard to see why they endure.

Another thing I’ve always admired about Martin and Eliza’s views on the music they play is their willingness to use it against modern narratives of purity and nationalism. Supporters of Folk Against Fascism, they were involved in setting up The Imagined Village as a multiracial, multicultural folk band that could create a sound that did justice to modern Britain — and historical Britain’s — reliance on immigration and the labour of its colonies. Just go and have a listen to Benjamin Zephaniah helping them re-work Tam Lyn. At this gig it was hard not to hear an anti-Brexit, anti-isolationist streak in the mischievous glee with which Eliza pointed out that, once upon a time, the popular English view was that Napoleon was their saviour, not Wellington… ‘The Grand Conversation on Napoleon’ comes across as a sibling to ‘Bonaparte’s Lament’, which Eliza recorded with her mother, Norma Waterson, on Gift (2010), providing a nice link between the two albums.

Musically, the two of them have a very particular dynamic; they’ve been playing together since Eliza was born, so there’s no attempt to make her into a substitute Swarb. And though she’s got her mother’s lungs, she’s a different generation of musician, and her voice and violin loop elegantly over and around Martin’s solid, syncopated guitar. Occasionally, as on the encore rendition of John Barleycorn, her enthusiasm doesn’t leave much space for Martin’s voice, but on the whole it’s a good balance, and even when they mess-up their intro they seem to be on the same wave-length.

An evening with a Carthy or a Waterson will always come with good stories as well as fantastic music. This was no different, with Eliza tending to provide the longer, meandering shaggy-dog stories behind the songs, and Martin occasionally expressing his enthusiasm for one melody or another, or muttering fond complaints at his guitar, which was prone to misbehave in the heat of the venue. It was a delight: consummate showmanship, peerless musicians and great storytelling. And, if you’ve any memories of seeing any Watersons or Carthys perform over the last decades, Eliza would really really love to know about it, so she can reconstruct her own family’s iceberg. From: https://ienthuse.wordpress.com/2017/10/02/review-martin-carthy-and-eliza-carthy-cambridge-junction/

Spirit - Dream Within A Dream

Los Angeles based Spirit were riding high after their eponymous debut album found some success and even hit the Billboard album chart's top 40. While they just released that album in January of 1968, after the entire group and their families having moved into a big yellow house in Topanga Canyon, north of LA in the countryside, they all resided together for the tail end of the 60s. The musicians in Spirit had the luxury to work together in a relatively serene and relaxed environment and diligently crafted a second album that came out the same year in December. The title The Family That Plays Together not only refers to the fact that drummer Ed Cassidy, a forty-something year old ex-jazz percussionist having been the step-father of the teenaged guitarist Randy Craig Wolfe or better known by his stage name of Randy California, but more due to the fact that the entire band along with significant others, children, pets, vices and idiosyncratic irritations were all shacked up together on a musical compound where they could practice their own 60s version of peace and love and take their music to new places hitherto unheard. And that's exactly what they did.

Spirit's sophomore album shows a more mature band sound that took the psychedelic rock, contemporary folk, classical and jazz- fusion elements of the debut and found them woven together in a tight musical tapestry with that off-kilter 60s psychedelia basted in a strong steady backbeat. One again Marty Paich made a reprise with his unique stamp with arrangements for string and horns which added the proper symphonic backing that with the jazz-tinged rock pieces created a veritable progressive rock template for 70s symphonic bands to expand upon. While Spirit never cranked out the hit singles, the opener "I Got A Line On You" was the exception as it was the band's only top 40 hit of their existence and the one track that everyone has surely heard if they have delved into 60s music at all. While that single and the closer "Aren't You Glad" add heavier aspects of rock complemented by Randy California's use of double guitar tracks, for the most part The Family That Plays Together is a more subdued mellow affair with the emphasis on exquisitely designed compositions that are cruising on California West Coast chill mode than anything close to the heavier Cream and Hendrix sounds of the day.

Part of Spirit's eclectic inspiration stemmed from the fact that Barry Hansen, who would become the kind of parody as Dr. Demento who specialized in novelty songs and comedy, had a huge collection of music in the same house that he was sharing which allowed the band to peruse the vaults for musical inspiration. And that is exactly what Spirit sounds like to me. There are so many tiny snippets of sounds that remind me of both past and future acts that one could rightfully write quite a lengthy thesis on the matter. The music on The Family That Plays Together is generally characterized by a strong groovy bass line that anchors the melodic development. The guitars and keyboards provide unique and progressive counterpoints with Cassidy's jazzified drumming style adding yet another eclectic layer. The band had mastered the art of harmonic vocal interaction much like The Beach Boys or The Mamas and the Papas but were more sophisticated than the average pop band of the era despite having cleverly crafted pop hooks that took more labyrinthine liberties.

During the year 1969, Spirit were at their popular (if not creative) peak with two hit albums and a top 40 single under their belt. While the band never hit the big time, during this brief moment in history, it was THEY who were the headliners while bands like Led Zeppelin, Chicago and Traffic were opening for them. While at the Atlanta Pop Festival, they performed to over 100,000 music fans in the audience and Randy California rekindled his friendship with Jimi Hendrix, with whom who briefly played in Jimmy James & The Blue Flames. The Family That Plays Together is an excellent sophomore release from Spirit. While the debut may have had a few more flashy jazz-fusion moments, this one has a more cohesive band sound which shows a clear dedication to finding the ultimate band chemistry at play. Laced with subtly addictive hooks and sophisticated progressive undercurrents, The Family That Plays Together is actually a little more accessible on first listen although it's slightly more angular than the average pop rock band of the era but still a testament to Spirit's unique musical vision. From: https://www.progarchives.com/album.asp?id=13050

Jonatha Brooke - Blood From A Stone

Boston Beats: How did you first get into music?

Jonatha: Well, let’s see, I always sang and I always copied things off of records. I got a guitar when I was 12 for Christmas from my dad, and started figuring out chords and making stuff up. I was in a rock band in seventh grade that my science teacher started, we were called Science Function, and I was always in the school choir or the acappella group or whatever. But it wasn't until Amherst College that I actually started writing songs and realized that I might have some kind of future in music, and that music was that exciting to me that I would go fully into it. Because up until then my main focus had been dancing, I thought I was a dancer.

BB: Do you remember anything about the first song you wrote?

Jonatha: Yeah, it was a class assignment. I took a composition course my sophomore year of college, and our first assignment was to take any E. E. Cummings poem, just anyone that we liked, and set it to music. That became my first song, and it’s actually on my first record with the Story, Grace and Gravity.

BB: When did you decide that music was going to be your career?

Jonatha: I kind of started falling into it in—I guess it was about ‘89 or so, when Jennifer and I were living in Boston. Jennifer Kimball, of The Story. I was still dancing a lot. I was in a bunch of modern dance companies, and Jennifer was working as a graphic designer. We made a demo tape and we started getting more serious about pursuing gigs and we were both juggling other careers. I think it was when we got our first independent record deal with Green Linnet Records, which then lead to Electra Records, that it was kind of like, wow, this is working you know, I think we have something here, and we might have to quit our day jobs and get on the bus.

BB: How did you guys first meet?

Jonatha: We met freshman year at an audition for the acappella group at Amherst College, The Sabrina's, and we both got in mostly because our voices blended so well together. So we were the soprano section.

BB: What was the story with the Goodyear Commercial, “Serious Freedom?”

Jonatha: That was ‘94, ‘95. I loved it; it paid the bills for two years. A friend of mine had written the jingle, David Buskin. He called me, I was in New York for something, and he called me and said hey, want to come down and hang at the session and see what I do. He has written some of the most memorable jingles that I ever heard. And I thought it might be a lark, and I’d go down and hang out and maybe sing some background vocals, and I ended up singing the lead. And there were all these jingle pros there, but somehow I got the gig. It was just completely a fluke, but it saved my butt financially for a year.

BB: You seem to be able to play a lot of instruments. Which do you feel most comfortable with?

Jonatha: Guitar, just because you can bring it anywhere, so it's the one I end up playing the most. I used to write pretty much 50/50 on keyboard and guitar, especially when I was first writing. And then the piano kind of fell away from me because I didn't have one for a while. Now I've got a Wurlitzer, and a big keyboard here in my little music room so I'm getting back to the piano, but I think I'm a better guitar player than I am a piano player.

BB: Tell me about your songwriting process. How does a new song usually come about for you?

Jonatha: I torture myself for weeks. I try to reassemble all the pieces of paper and the notebooks that I've been scribbling in for months and line them up with the melodies that I've been obsessed with in my head. Especially lately, they have been starting separately. A lot of times I won’t have a Dictaphone with me or anything, and I’ll just call my cell phone and leave these non sequitur ideas or these loopy melodies on my own answering machine. So my cell phone is just clogged with 20 different melodies that I've thought of over the past few weeks.

BB: What are some of your favorites of your own songs? How did they come about?

Jonatha: It changes day-to-day but I love on the new record, No Net Below, and I love Better After All. Last week it was Paris from Plumb and Walking from Steady Pull. One I wrote recently for a movie, it really was kind of weird. All of a sudden, it was there on the page, and I had no idea how I really came up with it, and it was one of those all at once ones, too. The movie is called Hide and Seek, it's a De Niro movie. They ended up not using it; it was so perfect, I was so bummed. I love this song, it will end up somewhere on a record or iTunes because it so creepy, I had to really put myself in a really creepy horror mode, and sing like a little girl and make it really scary. It was fun producing it as well as writing it.

BB: What are your own musical influences? What are your favorite albums?

Jonatha: I have to say classical music influenced me, because it was always on my stereo growing up. Rachmaninoff, and Chopin's Ballads. My mom would play opera a lot, and I would walk around the house trying to sing along. I associated music with great emotion because my mother would always cry when she heard beautiful music. My brothers brought home the Beatles, The Who and Neil Young and Stevie Wonder and Joni Mitchell they were my next sort of palette. My mother and I, the thing we shared the most was the Mama and the Papas. I loved the harmonies. There were a couple of records that I just wore out, The Sound of Music, God Spell and West Side Story. I love Radiohead, and pretty much anything they've done. I love Coldplay I know that it’s probably not cool anymore to love them but they're still frickin’ great. I love this guy, Teitur, I think he's from the Fair Isles. I just really like his record, it has an innocence and beauty to it. Damien Rice I like. I'm trying to think of some chicks that I'm into lately. I like Casey Chambers, she's very twangy but I just love her. And I love Gillian Welch.

From: http://www.bostonbeats.com/Interviews/InterviewBrookeJ.htm

Matthews' Southern Comfort - Blood Red Roses

Misery loves company, and for many songwriters, it just comes with the territory. At least that’s how Iain Matthews sees it. The founding member of Fairport Convention and Matthews’ Southern Comfort uncovers deep-seeded anger, pain and frustration over relationships and career ups and downs in his latest solo album, “The Dark Ride” (on Watermelon Records). For the 48-year-old English-born singer-songwriter, it has been a long dark ride. “It’s probably unfair to say songwriters have an exclusive right to it,” Matthews said recently from his home outside Austin, Texas. “But I think for anyone that is artistic in any way, as a career, there’s a lot of soul-searching going on because you’re constantly looking for something better.”

Matthews wanted something better after his solo career waned in the ’80s and he had moved to Los Angeles, working as an A&R man for the Island and Windham Hill labels. The title track addresses that period in his life. “What better place to be miserable?” Matthews said. “My answer was to go into therapy. I did that for four years. I fought it like a terrier. People would suggest (therapy) to me and I would say, ‘Naw, I can work it out.’ Therapy was the best thing that I ever did for myself.” When going through his mother’s things after her death earlier this year, Matthews found a high school report card from 1961. Pictured in the disc’s liner notes, the report card contains a teacher’s comments on the restless youth: “Must learn to think – concentrate”; “Must get that chip off his shoulder”; “Has ability, fails to use it; bone idle & a nuisance to himself & other people.”

“I just wasn’t interested in school. It was just one big putdown,” Matthews said. “All I wanted to do was play football and write short stories.” He dropped out of school, then joined a South London surf-music group. Born Ian Matthew MacDonald, he used his middle name professionally to avoid confusion with King Crimson’s Ian McDonald. (He now goes by the Gaelic spelling of Iain.) He then established himself in the folk-rock movement by forming Fairport Convention with Richard Thompson and friends.

Weary of the folk scene, Matthews left the Fairports after two albums and formed what would become the country-flavored Matthews’ Southern Comfort. Just as their second album was released, a track never intended for the album – a version of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock,” first recorded during a BBC appearance – took the nation by storm. It quickly rose to No. 1 on the British pop singles chart, staying there three weeks, and later charting at No. 23 in America.

“That wasn’t what I wanted … that was the last thing I wanted,” Matthews said. “It created all this peripheral stuff that took up my time. What would’ve been time learning to be a songwriter, it became time spent doing interviews, photographs, tours and appearances.” Matthews bailed out at the peak of the group’s success in 1971. “I still have people who hate me to this day for leaving the band,” he said. “I kind of pulled the plug on them.” Matthews still has a fondness for “Woodstock” and the early music he made. And even though he went on to score a No. 13 hit with “Shake It” in late 1978, he never matched the impact of “Woodstock.”

Only recently has he even considered himself a true songwriter. “I have a terrific attachment to ‘Skeleton Keys’ (1993), the one before this album,” Matthews said. “It was the first record I had done where it was entirely my own material, and the beginning of my sort of openness and soul-searching is on that record, stuff about my career and my home life. “I still have an emotional tie to that record, but people keep telling me that (‘The Dark Ride’) is my best record yet. … I’m coming around to believing them.” From: https://www.pauseandplay.com/iain-matthews-finds-his-southern-comfort/

Etta James - Tell Mama

As the summer of 1967 approached, things did not look auspicious for 29-year-old Etta James, who had spent recent times detoxing at the USC County Hospital and also had spells at Sybil Brand, the women’s prison in Los Angeles, for drugs offenses. “Nothing was easy then,” James later recalled. “My career was building up but my life was falling apart.” Amid such turmoil, no one, not even Etta James, could have predicted that she was on the verge of recording Tell Mama, one of the finest soul albums of the 60s.

James had been at Chess Records since 1960 and Leonard Chess wanted her to record a new album for his Cadet Records subsidiary. He took her to Sheffield, Alabama, to record at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, under the direction of acclaimed producer Rick Hall. As well as keeping her away from the temptations of life in the city, it would also provide her with new musical inspiration. The move paid off and the result was a masterpiece. Hall’s success in that decade – the foundation of what became known as “the Muscle Shoals sound” – was built on a special alignment of black singers and white musicians in a time and place when race relations were dangerously strained. Many of the greatest R&B songs of the 60s, by artists such as Wilson Pickett, Clarence Carter, Percy Sledge, Aretha Franklin, and James herself, were recorded at FAME under Hall’s supervision.

Among the famed rhythm section – dubbed The Swampers – were Jimmy Ray Johnson and Albert “Junior” Lowe (guitars); Roger Hawkins (drums); Barry Beckett and Spooner Oldham (keyboards); and David Hood (bass). They were supplemented by a pulsating brass section of Gene “Bowlegs” Miller (trumpet); James Mitchell and Aaron Varnell (saxophones); and Floyd Newman (baritone saxophone). Hood, the father of Patterson Hood, of Drive-By Truckers, recalled, “The Chess brothers wanted her to record where there was a chance of getting a hit, but also where she would be isolated from a lot of the temptations and distractions that go on in Chicago or New York or somewhere. We didn’t know it at the time, but Etta was pregnant [with her first son, Donto]. She was a wonderful singer, a really great singer. She was not that much older than any of us, but she seemed older because she had been around. She had been a professional since she was about 14 or 15 years old, working with Johnny Otis and different people in Chicago and California. So she seemed much more worldly than her age.”

The album’s opening title track, a song Hall had recorded a year previously with Clarence Carter (as “Tell Daddy”), is sensational. The improved recording technology at FAME meant that some of the problems of the past – when her higher notes could get distorted – were solved, and Hall achieved an unprecedented clarity on “Tell Mama” and the following 12 songs. “Tell Mama” was released as a single and reached the Billboard R&B Top 10. The second track, “I’d Rather Go Blind,” is a memorably agonized ballad of loss and jealousy. James’ brooding vocals, soaring over the mesmerizing pattern of rhythm guitar, organ, drums, and swaying horn line brought out the visceral pain of the lyrics. When Leonard Chess heard the song for the first time, he left the room in tears. In her 1995 autobiography, Rage To Survive, James recalled how she had helped her friend Ellington Jordan complete the song. Jordan wrote the song in prison when he was feeling overwhelmed and “tired of losing and being down.” James gave her co-writing credit to singer Billy Foster, supposedly for tax purposes, a decision she came to regret following later money-spinning covers by BB King, Rod Stewart, Paul Weller, and Beyoncé.

There are plenty of other fine moments on a consistently strong album that includes sizzling covers of Otis Redding’s “Security” – written for his 1964 debut album – and Jimmy Hughes’ “Don’t Lose Your Good Thing.” She also brings great verve to Don Covay’s song “Watch Dog,” which is only two minutes long, and “I’m Gonna Take What He’s Got.” Elsewhere, the sheer power, nuance, and depth of emotion in her voice brought to life songs such as “The Love Of My Man,” which was penned by Ed Townsend, the man who also co-wrote “Let’s Get It On” with Marvin Gaye. Tell Mama is not an easy listen. James seems to be living the pain of songs such as “It Hurts Me So Much” (written by Charles Chalmers, who sings backing vocals on the album), and even the jaunty upbeat melody cannot hide the ferocity of her delivery on “The Same Rope” as she sings “The same rope that pulls you up/Sure can hang you.”

Though Tell Mama was a commercial and critical triumph following its February 1968 release, life did not get easier for James in the successive years. For a time in the 70s she returned to Chess Records to do desk work, though drugs and drink remained a lifelong blight. Happily, however, she had a career revival in the 90s. James’ reputation as a singer will remain, especially with a wonderful album such as Tell Mama. As Rolling Stone Keith Richards said: “Etta James has a voice from Heaven and Hell. Listen to the sister and you are stroked and ravaged at the same time. A voice, a spirit, a soul, that is immortal.” From: https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/tell-mama-etta-james/

Friday, June 28, 2024

Diamanda Galás - Das Fieberspital (The Fever Hospital) / Eyes Without Blood 1984 / The Litanies of Satan 1985

Diamanda Galás - Eyes Without Blood 1984

Diamanda Galás - The Litanies of Satan 1985

‘Free Among The Dead’, from The Divine Punishment, (1986)

I used Biblical texts because I was interested in the anatomy of a plague mentality. Some were from Leviticus, a book of laws which indicated how to separate the clean from the unclean. I had just seen the first person I’d known to have AIDS die in New York, and when I came back to San Francisco, I started working on the text of Psalm 88. It riveted me and shocked me because it starts out, “O Lord, God of my salvation, I have cried day and night before Thee, let my prayer come before Thee, incline Thine ear unto my prayer.” But then it says, “Free among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, whom Thou remembers no more, and they are cut off by Thy hand.” Those verses within the Psalm terrified me. A lot of my work is concerned with the transition between life and death. By this, I do not mean anything spiritual, but the man who’s walking up the stairs to the gallows, this absolute dread – I seem to select works that address that death chamber and that particular fear. I recorded half of The Divine Punishment in San Francisco using ring modulation and other processes on my voice, and played a very large grand piano and synclavier. I recorded ‘Free Among The Dead’ first, and then I went to London to do the second part with Dave Hunt. He’s definitely a person who believes in the first take.

It’s interesting you record in one take, because you’ve released a lot of ‘live’ albums but I feel that there’s not much of a delineation between them and the ‘studio’ records.

I’m very glad to hear that because there was one person who was saying, ‘oh my God, another live album’ and started to complain about all the songs I hadn’t recorded yet. Why don’t I send you all the songs I’ve performed and I haven’t recorded? How about that? You can be more depressed, you know? It’s just like, fuck off, you imbecile.

‘Blind Man’s Cry’ from Saint Of The Pit (1986)

Before he died, my brother handed me a book of French poets and I selected this one, Tristan Corbière’s ‘Blind Man’s Cry’. When you see the large eyes of someone who is powerless and knows that he can’t escape the cage he’s in… I will never forget that. ‘Blind Man’s Cry’ was especially shocking, because the words are so definitive of what I’m talking about. Corbière was deaf, and there is something interesting about a deaf poet writing ‘Blind Man’s Cry’, because he understands the concept of hopelessness. It is devastating – I say this because I think a poem must be devastating. It must say, ‘Diamanda, wake up. Wake up before it’s too late!’ This is why I do the poems I do, because they are like the dead offering me a hand. I really mean that. It’s why I like to work in the dark at night. I come downstairs in the dark, I have a purple light on and I start working. I find it really annoying to wake up in the morning and open the door and see happy people on the street. I have to slam it right away. It hurts my skin. When I talk to somebody who understands, I become someone different, because I can present myself as extroverted. When I get off the phone, I will go back to that other self. This poem is essentially saying, ‘I am nailed here and there is no sympathy, there is no empathy from anyone’. He’s asking death to hurry up and he’s begging the birds, the crows to come.

You Must Be Certain Of The Devil (1986)

I finished the first part of what became the Masque Of The Read Death trilogy and brought it home. That’s when my brother was very ill. My feelings towards my brother played a huge role in the second part, which ended up being less a book of laws and more of a cry. I chose poems that are incantational, desperate cries – I’m not saying that to be dramatic. I’m saying that because that’s what they are. They’re cries from the hole. I don’t know whether at that juncture I determined there was going to be a third record, but I got the room temperature of the virus in the United States, because in London and Berlin, people would just laugh at me when I told them what I was working on. I generally didn’t discuss it because they would just laugh and laugh – these were straight musicians, it must be said. The reason that I worked with Erasure was because we understood each other politically. I wasn’t speaking to someone who put his hands over his ears and didn’t want to hear [music relating to AIDS], who was nauseated and thought of it as a kind of a faggot special interest group. A lot of these straight guys, they were such a pain in my ass to be around because they were cornier than a motherfucker – and some continue to be. It’s really curious to me how you can write so many songs about teardrops falling from the ceiling – it’s like, hey, buddy, okay, you suffered with this girl. How many songs do you have to fucking write to get over it? I can’t write material like that. I don’t want sympathy from anyone. It doesn’t really affect me, but it made it impossible for me to hang out with a lot of musicians. There are other things that are happening in the world. I’m not saying that one has to write political songs. I don’t even write political songs. They’re more and more psychological to start with and then they become political. When I was in London I saw a particular emotional reaction among many people to the stigma of AIDS, to the idea of something being dangerous. I’m not complaining about it because when you do work that you feel possessed by, you’re not losing time. If you do work that’s for somebody else and you’re mid-range about it, then it could be a waste of time. I have never felt that I had the time to waste. I, like a lot of Greeks, obsess about death every day. It’s in the genes. Death is in the genes.

‘See That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ from The Singer (1992)

My interpretation of ‘See That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ is ‘don’t add anything. Don’t spread rumours about imagined follies of mine or imagined transgressions of mine. Keep it clean, ma’am. Don’t fuck around.’ You don’t think about how to interpret a song like this. You just sit and it comes. I get right down the chord changes and I start. That song came very quickly. It is magnificent and you can see how it can work within an AIDS phenomenology because people die and then suddenly have no control over their legacy. Journals can be opened and I think of all the essays and letters I’ve written on my computer that I’m going to have to delete. And I just say, I don’t want to do it today, but when are you going to have time? There are so many things in my house alone that I’ve collected over many years. I’ve got to get rid of a lot of this stuff. What do I keep? Where do I send it? To the dead person, the most painful thing would be having a relative, a mother for example, read journals that were composed from the bathhouse. Why the fuck would you want your mother to read that? I won’t get personal with it, but there was a time when that was a moment. And so that’s what that poem is about.

Vena Cava (1993)

This concerns a patient who is in hospital with AIDS, and that person has reached a level of depression that is unreadable and can be confused with AIDS dementia. It’s not possible to medically test for that until an autopsy, but doctors would make guesses. If you had something on your chart that said you had dementia, then you had no control. You had no say in those little investigations that doctors will do on a soon-to-be-dead corpse – spinal taps and so many invasive procedures. These can be done while the person is alone, in a delirium and defenseless. That is what this piece is about, because albeit it wasn’t discussed that much, I felt that it was imperative for a person’s friends to say, ‘no, he does not have dementia, he’s very depressed, and why wouldn’t he be?’ The fluorescent lights that never go off, the cold of the hospital, the nurses that keep waking him up and saying stupid things, and visitors that will say the wrong things. Now, about that I would always tell people, ‘go to the hospital. Yes, you may say the wrong thing, but the most important thing is for the person to remember that you were there, and that you love them’. Some people would say ‘hospitals aren’t my thing’. What the fuck are you talking about? You’re an activist, but hospitals aren’t your thing. You just fucking try me with that one. Come on! A lot of my work is about trying to seek a dignity for people in death, with the same voice I say that it is fatiguing to listen to parlour room romance stories. Yeah OK, he left, and he came back, and then he left again? Well that is really so far out. What can I fucking say?

‘Last Man Down’ from This Sporting Life (1994)

I discovered how amazingly John Paul Jones performed the lap steel. And I said, ‘what? You play like that and you haven’t considered playing it for the record? Well, you’re playing it’. That’s it. He just sat down and played the shit out of it and it was so gorgeous – that, for me, is one of the great music pieces on the record. The title is what my gay husband used to say while his friends were dying – ‘I guess I’ll be the last man down’.

‘Burning Hell’ (first version on La Serpenta Canta (2003)

I did this song twice on La Serpenta Canta because every time I’ve performed it, it has been completely different. I do that with a lot of songs. That’s when people say they’re covers, I think who the fuck are you talking to? You’re talking to an improvising musician, just as Ornette [Coleman] would do a version of something completely different every time and it would never be called a cover version, so stop it, don’t even try that one. So I put two versions on the album and then some guy wrote, ‘it remains to be seen why she would repeat herself on this record’. Yeah, well, it remains to be seen why you can’t even fucking hear the song both times and realise the difference. That was a blues tradition and it’s funny, because people say ‘well, they just wanted to be paid twice’. Right, take it to the bank, you asshole. There are so many ways to do a song – I’ve had to do the same song during two sets in a night and of course, I do the songs differently. Why would I want to do them the same? I’d be bored. ‘Burning Hell’ – the man is just saying ‘I don’t know what’s happening to me, maybe I’m going to burn in hell’. He’s talking about asking the preacher, ‘what can I do?’ or ‘what’s going to happen?’ That preacher doesn’t know. Nobody knows.

Do you think because you released albums on Mute and you were around people who write conventional songs that people when responding to your music were confused?

When I released Divine Punishment, man, some music critics who were pretty big in London just hated it: ‘This isn’t music. I don’t know what the hell this is. It’s not music’. Okay. All right. So then I do the Plague Mass and Masque Of The Red Death, which had established a context for it, and having performed it at St. John the Divine during the height of the AIDS epidemic everyone knew what was going on by then. When that record came out, it was very well respected, but Saint Of The Pit was hard for people to figure out and You Must Be Certain Of The Devil – the reviews on that just make me howl.

‘Holokaftoma’ and ‘Hastayim Yasiyorum’ from Defixiones – Last Will And Testament (2003)

‘O Prósfigas’ [on new album In Concert] refers to the refugee, who is on a death march from Turkey into Aleppo, Syria. That’s where during the genocide of 1914 to 1923 they walked the Armenian men, the Greek men, the Assyrian men, the Yazidis, the Azeris – everyone who was not Turkish was walked to their death. On the roads were mountains of skulls in pyramids for them to see so they knew what their death was going to be. The Greek genocide was called the Holokaftoma. It means, ‘burning of the whole.’ ‘Holokaftoma’ is a Greek word that refers exclusively to the Asia Minor Genocides between 1914 and 1923. Last month search engines removed our genocide, and the word is only used to refer to the Jewish Holocaust as a translation. This second genocide took place between 1941 and 1945. The word ‘Holocaust’ comes from our word ‘Holokaftoma’. These are two different genocides! People have to understand that our genocide preceded the Holocaust. The Holokaftoma was the model that Hitler used, which he got from his mentor Kemal Attaturk, who counselled him saying, “Who remembers the Armenians?’ Now this is being erased, if the word ‘Holocaustoma’ refers only to the Holocaust of the Jews and no longer the ‘Holocaustoma’ of all of us between 1914 and 1923. And that is really egregious. I would say that in large part, Erdogan is responsible for that, because he and the EU have a massive press campaign to destroy Greece. Part of that campaign is to say that the Greeks are irresponsible about bringing in the refugees and caring for them, but you’re talking about a country under austerity measures from the EU, who can’t get more than $50 out of the bank at a time, and people who don’t have work anymore, and the payment for work is so low. And then at the same time, they’re trying desperately to take care of the Syrians. There are many Syrian Orthodox who have come in, who have been relieved to be in Greece. The truth is that many of the Syrians have been rerouted over many years by Turkish police boats to the open harbours of Greece, because Erdogan wants to ruin Greece, and he hates the Arabs. He believes in Turkishness. There are institutes for Turkishness where they say the books written by Homer, by Socrates are written by Turkish authors whose real names are ‘Sokrati’, ‘Omeron’, and so forth. They claim that the music is now Turkish music, but it was the mixture of Greek music, Byzantine music and Arabic speakers music, Armenian music, Azeri music. These musics that were made together were hashish music or outlaw music, a place where people would get together and sing dark music, this dark music that spoke of suffering and fear. Erdogan’s threat to Greece is ‘don’t make trouble because any night we can go back to Cyprus (meaning the invasion of Cyprus), and any night we can go back to 1914 or 1922, the burning of Smyrna’.